The first reviews of the documentary Prime Minister are in.

Since her valedictory speech in April 2023, Jacinda Ardern has sought largely to stay out of the spotlight. In 2025, however, she’ll be back in the headlines – or bookshops and cinemas, at least.

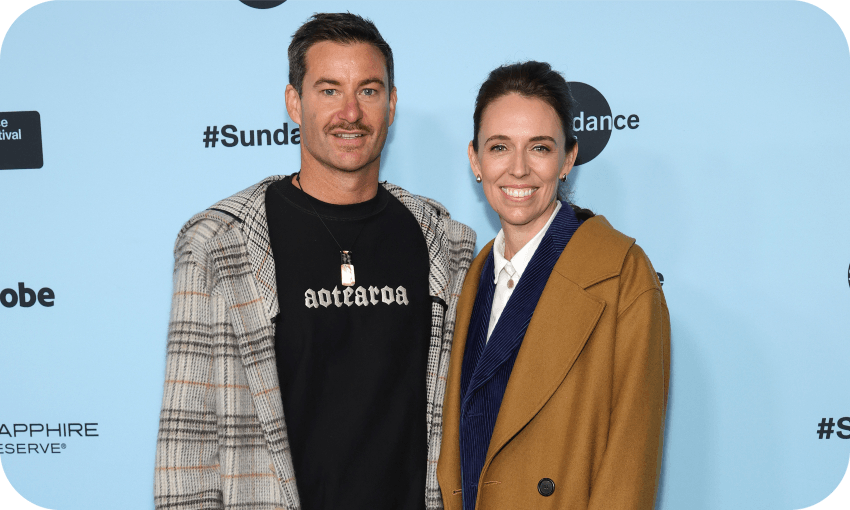

Last week, Ardern announced that her memoir, A Different Kind of Power, will be published in June. And two documentaries also have the former prime minister at their centre. One of those, supported by the Film Commission, is slated for an August release. The other, which by contrast has Ardern’s involvement and implicit endorsement – her husband Clarke Gayford is credited as both a producer and a director of photography, and contributes plenty of family footage to the project – is currently playing at the Sundance Film Festival.

The film, titled Prime Minister, is part of the World Cinema Documentary Competition at the Utah event, and Ardern is among those attending the festival. What are the reviewers saying so far?

Writing for IndieWire, Harrison Richlin awards a “B” grade to the film. Directors Michelle Walshe and Lindsey Utz had presented “a compelling what-if to Americans now dealing with another four years under a ruthless tyrant by showcasing the capable leadership and everyday life of former New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern during her six-year term, as well as where she is today post-resignation,” he writes. “The documentary acts as an intimate study of what it means to serve others when it seems like the world is falling apart and to be a partner and mother at the same time.”

For all that, it ultimately “feels like a film that would’ve had more impact if released a year ago, but today reads as a tragic depiction of yet another experienced, thoughtful woman whose determination to do good, both by her family and the country she represents, is steam-rolled by the horror and bigotry other individuals wish to bring on the world”, he says.

Caryn James puts it differently, writing in her review for The Hollywood Reporter that the release is “timelier than anyone might have expected. It would be a bit of an exaggeration, but just a bit, to say it trolls Donald Trump. It’s no accident that it includes deliberate, pointed contrasts that position Ardern as the American leader’s exact opposite in their approaches and objectives.”

James commends the filmmakers’ ability to “juggle the personal and political”, but adds one reservation: the coverage of her resignation as prime minister is “both compelling and too partial”. She concludes: “But even with its omissions and glossiness – a typical side effect of insider access – Prime Minister’s portrait of Ardern is so persuasive it might make you wish you could vote for her.”

IndieWire’s Richin offers a similar critique. “Though it’s not featured as part of the narrative, in resigning as PM, Ardern opened the door for Labour to suffer a landslide defeat in the next election, marring her own legacy for the sake of her mental health and as a response to those who stood in opposition to her,” he says. “As she packs her office sporting a Portishead T-shirt and reveling in the presence of her now fiancé and their daughter, we can see her joy slowly start to flow back in, forcing us to wonder if any good person can actually govern in a world where politics have become seemingly ruled by those who are loudest and most out for themselves.”

Amber Wilkinson of Screen Daily is impressed by “an eye-opening insider perspective that comes as a reminder of what conviction politics looks like when it is maintained even under extreme pressure, as well as being a celebration of feminism”. Prime Minister, “as much about the person as the position she held”, she writes, “might just restore some of your own faith in politicians”.

“Intimate but simplistic”, is the headline in another trade staple, Variety. “Gayford’s proximity is a double-edged sword, one the rest of the production also wields, in terms of its limited political approach,” writes Siddhant Adlakha. “However, as a portrait of struggles in the seat of power, the film presses all the right emotional buttons.”

He concludes: Prime Minister may verge on hagiographic in its telling, but as a tale of political mythmaking – and a young woman in a world of right-wing strongmen – it’s greatly assisted by its intimate documents of Ardern. Since these are captured by her closest confidant and biggest supporter, they come with all the flaws and flourishes that living in a leader’s proximity provides.”

As for Ardern’s personal assessment, in a Q&A session at the Sundance festival on Sunday, she said: “I saw the final cut of the film yesterday. I cried through most of it, and I’m not sure if that’s equivalent to laughing at your own jokes. I was very emotional watching it. I credit the storytellers for it. I hoped that the film would humanise politicians, those who are public servants, and leadership, but I never thought it would humanise me. When I watched it, I just saw myself as someone who was trying to do their best.”