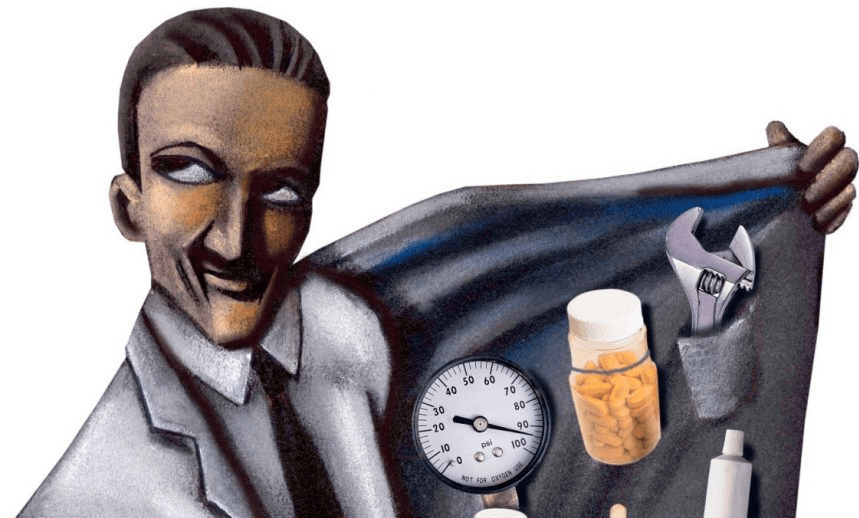

We need a new law to plug the big gap in our regulation of health products, argues Mark Hanna

Winston Peters has decided that we don’t need an incoming anti-quackery bill. He’s wrong.

In a press release earlier this week, Peters called for the poorly named Natural Health Products Bill to be scrapped:

“This Bill is regulatory overkill and the more New Zealand First looks into it, the more we realise the Natural Health Products Bill is a solution looking for a problem.”

“We believe the regulation of Natural Health Products and Supplementary Products is adequately provided for under other legislation.”

At first glance, this isn’t unreasonable. After all, we already have the Medicines Act and the Fair Trading Act to protect us from misleading claims about health products, right? Well, that’s true, but the best rules in the world don’t mean a thing if they’re not well enforced.

And, well, ours aren’t.

The Medicines Act prohibits the sale of any medicine that hasn’t been approved. Promoting a product in a way that implies it’s intended to diagnose, prevent, or treat health issues in humans is enough to make it treated as a medicine by the regulation, so it can’t be sold that way without approval.

But there’s an uncomfortable middle ground, where misleading health claims are made but they’re not serious enough for Medsafe, the regulatory body responsible for enforcing the Medicines Act, to decide to get involved.

The first line of defence in cases like this is the Advertising Standards Authority. The ASA is great considering what it is, but there are several problems with relying on them:

- They rely entirely on receiving complaints from the public.

- They give a free pass to a certain class of health claims that I think can be very misleading.

- If they uphold a complaint, there’s nothing they can do to enforce it.

If you see an ad that says a product “supports healthy immune function”, for example, that doesn’t actually mean it does anything for your immune function. From the regulatory perspective, it just means it probably won’t mess with a healthy immune function – if that’s what you already have. Though they aren’t required to provide any evidence for that.

This class of health claims, which often use weasel words like “supports”, are commonly given a free pass even in cases where they seem clearly misleading. They’re the “wink, wink, nudge, nudge” of the health industry – trying to convey a different impression to regulators and the public.

But what about the Fair Trading Act? It essentially says you can’t make any claim about a product you’re selling without a good reason to believe it’s true: “A person must not, in trade, make an unsubstantiated representation.”

Maybe Peters is right. That should handle all of these cases of misleading advertising even when the Medicines Act and the ASA fall short.

The problem is, it doesn’t. Because there is far, far too much misleading advertising for the regulator – the Commerce Commission in this case – to take action against anything but a tiny section. They’re more likely to pay attention to issues that could affect New Zealand’s reputation as an exporter, such as false claims that a product has been made in New Zealand, than they are to address misleading health claims.

Medsafe has essentially the same problem. They greatly prioritise safety issues over issues of misleading marketing. This makes sense, but they don’t seem to have the resources to take action on the lower priority misleading marketing issues.

The result is a huge number of misleading health claims.

At the Society for Science Based Healthcare, a volunteer consumer advocate organisation that I chair, we do our best to fight this. We’ve made over 240 successful complaints about misleading health claims to the ASA since 2012. Just last week, the ASA released decisions on nine more successful complaints. But our efforts have hardly scratched the surface.

When we’ve tried alerting the Commerce Commission or Medsafe instead of the ASA, the results have almost without exception been disappointing.

A complaint that I laid with Medsafe about a company selling “harmonized water” to treat allergies, asthma, and more has been languishing without progress since September 2014.

The Commerce Commission recently took two months just to tell me they won’t do anything about a Christchurch homeopath who’s refused to comply with multiple complaints that have been upheld by the ASA.

It’s clear to anyone who engages with this system that there is a large gap in our regulation of health products. The Ministry of Health came to a similar conclusion in 2007, when they undertook an overview of the New Zealand complementary medicines industry. The overview found that 78% of companies selling these products were not compliant with existing regulation.

Yes, that was a decade ago, but there has been barely any change since then. I’ve been involved in anti-quackery activism for half of that time, and it seems to me that it’s just as prevalent now as it was five years ago.

Winston, if you have any more recent data please let me know. My email address is easy to find.

The vast majority of products at the centre of this problem fall into the confusingly named category of “natural health products”. This is the area that the Natural Health Products bill and its associated guidelines are intended to address.

They’re not perfect, by any means. For example, homeopathic products are explicitly excluded from the scheme, even though they’re both completely useless and often promoted with health claims. But overall it is certainly a step in the right direction.

Products will have to be registered to be sold, and there are requirements around things like ingredients and evidence. My favourite part of the bill is that each of these notified products will have to put a summary of the evidence for any health claims made about it in a publicly accessible database. Here’s what the proposed guidelines say:

“Product notifications will need to include a reference to a website with a summary of the evidence supporting the health claims for a product so that consumers can easily see the basis for the claims.”

This is a rare case where I, as an anti-quackery activist, agree with “natural health” industry bodies. They want the improved reputation that comes from regulation; I want better protection against quackery for New Zealanders. With this bill, we could find a happy middle ground where those products which are supported by evidence can be sold, and we have useful protective measures against being misled about products which aren’t supported by evidence.

The Spinoff’s science content is made possible thanks to the support of The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, a national institute devoted to scientific research.