When private companies are paid to own and operate public transport, who wins? Not the drivers, nor the passengers – and certainly not the planet, write Wellington councillors Tamatha Paul and Thomas Nash.

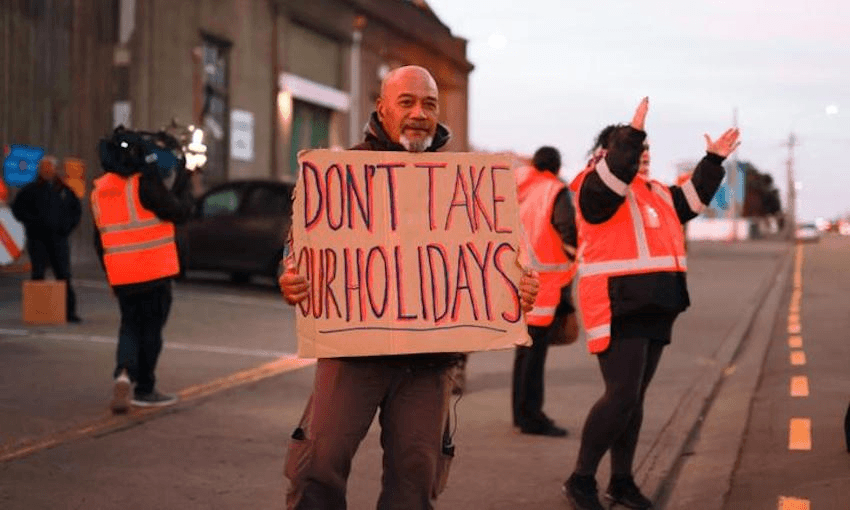

Last month’s Wellington bus driver lockout at the hands of their employer, NZ Bus, sparked a fresh set of questions.

Before then, people had, understandably, focused mostly on when the bus was coming, but now they wanted to know more. How come an Australian private equity firm owns around half the buses in Wellington, plus a bunch in Auckland and Tauranga? Why don’t bus drivers already get paid a base rate above the living wage? Why would bus drivers sign new contracts they consider worse than the ones they are currently on? Why are companies making private profit from public transport and how do they end up owning these buses that are ultimately paid for with public funds? Who was the genius who thought up this system? And, importantly, how much of a strategic climate risk does private ownership of buses pose?

Wellington bus drivers were served with a lockout notice on April 22 in response to the drivers’ union’s plan for a 24-hour strike the next day. This followed a breakdown in collective agreement negotiations with NZ Bus, which is owned by Australian private equity firm Next Capital.

Wellingtonians were dismayed by the terrible treatment of our local bus drivers, who were locked out of their livelihoods while demanding the dignity of a living wage base rate of pay. Successive national reforms have squeezed the state out of public transport and now public agencies like councils and central government pay private companies to own and operate our public bus services. Who has benefited from these reforms? Passengers haven’t, and nor have drivers. Maybe some shareholders have. The climate hasn’t.

In Wellington pretty much everyone wants action on climate – 92% of us. As a city, we are always eager to get out onto the streets and demand justice from our leaders through kaupapa like the School Strikes 4 Climate. Truth is, when it comes to our cities and our increasingly urban population, there is no one magic button for climate action. Instead, the struggle for our climate is happening right now and our bus drivers are at the coalface.

Transport emissions make up more than 40% of Wellington’s emissions, mostly from private vehicles. The best way we can give people more options is to increase the frequency, reliability and accessibility of fully electric public transport, alongside safe, connected cycling and walking infrastructure. Let’s give people a wide range of transport options and not shame those who rely on a private vehicle – or any other mode – to move about the city.

A few years ago, our city was shaken by the bustastrophe, where major network changes at a time of driver shortages had a negative impact on people’s day-to-day lives. Since then, the regional council – which manages the public transport network and sets routes and fares – has taken big strides to restore public confidence. One of those recent moves was setting the living wage as a base rate for bus drivers. Moving more people onto public transport means massively increasing the availability and frequency of the bus service. That requires more drivers who feel valued in their job.

However, Next Capital seemed to choose profit over people, trying to force through new contracts that bus drivers said took their pay and conditions backwards. The company locked out drivers, presumably prioritising the 25% returns they promise shareholders on its website over fairness and dignity for the people getting us all safely from A to B. The union applied to the Employment Court for an injunction, which was granted, but NZ Bus has not ruled out taking further action.

The current public transport arrangement, where private gain is extracted from workers and public funds, is symbolic of the struggle for climate justice. It makes choosing the best option for our planet more expensive because of the need to pay for profit margins. This is self-defeating and unnecessary. The amount of profit that bus companies make, often at the expense of hardworking people – both drivers and the public – could well be enough to provide free public transport for every Community Services cardholder in the country.

To scale up bus services we need to change the public transport legislation at a national level and bring our buses back in-house. The Ministry of Transport is working on options to change the “Public Transport Operating Model” – the rules councils follow to organise public transport. As councillors working on climate in Wellington, we have some recommendations.

First, provide for public ownership and operation of bus services by public entities. Public ownership allows national coordination tailored to local needs, so in Wellington we might see a public Wellington bus corporation.

Second, develop a nationwide agreement on fair pay and conditions for drivers and public transport workers so that everyone gets a decent deal no matter who their employer is.

Third, make a nationwide plan for a large-scale purchase of electric buses, with strict procurement standards on human rights and environmental protection, ideally using bus builders based in Aotearoa.

These changes will take time to come into effect, with existing contracts for bus services in place until at least 2024 in Auckland and at least 2027 in Wellington.

When we all demonstrate and support the intersecting ways that properly resourced, publicly owned bus services can help us achieve a valued workforce, more liveable cities and real climate action, then the sooner we will be there. Thank you, drivers!

Tamatha Paul is a Wellington city councillor and Thomas Nash is a Wellington regional councillor.