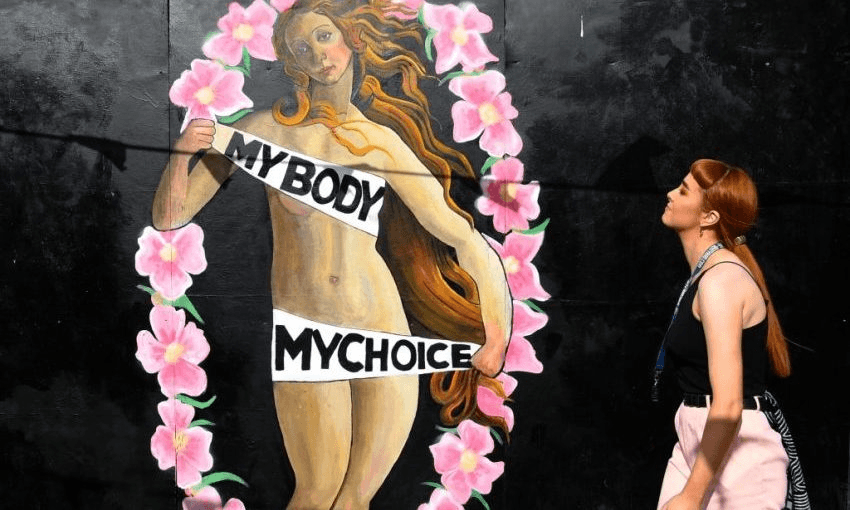

This week, a bill that would ensure pregnant people seeking abortion don’t have to be confronted by angry mobs outside of clinics is expected to have its first reading. Terry Bellamak explains why safe areas are so crucial for vulnerable patients.

Last March, New Zealand legalised abortion. The new law changed many things for the better – no more seeking approval of certifying consultants, no more having to lie to come within the grounds in the Crimes Act. But due to a procedural misstep, safe areas did not make it into the final version. MPs asked too late for a roll call vote. To be fair, it was late at night.

Louisa Wall’s member’s bill, the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion (Safe Areas) Amendment Bill 2020, would rectify that misstep.

Safe areas are designated spaces, at most 150 metres wide, around premises where abortions are provided where it is unlawful to intimidate, obstruct or interfere with people who are there to receive abortion care or provide it.

If you think that sounds like behaviour that ought to be unlawful anywhere, I agree.

People often tell me about their abortions. Almost everyone mentions harassment outside the services. Whether they encountered it or not, they anticipated and feared it. Rather than being stared at or even yelled at, they feared the escalation to violence incipient in such encounters.

Being targeted outside an abortion service feels a lot like street harassment, something almost everyone who has walked around this planet looking female has a visceral understanding of. It’s not about the stares, the whistles or the trashy come-ons. The threat of violence is foundational to the act of invading someone’s attention with sexist stares, whistles or words.

It’s bullying.

What happens at these ‘protests’?

Most anti-abortion harassment includes gory posters purporting to be aborted foetuses. These usually depict foetuses at or near full term, even though 94% of abortions in New Zealand happen before the 14th week, when foetuses don’t look much like the posters. Many people would agree they are not appropriate in a public place.

The actions of harassers sometimes take a turn for the dramatic. High-pitched cries of “Mummy, please don’t kill me”. Shouts of “murderer” or “have mercy on your baby”. Or pelting people with baby doll parts daubed with red paint.

Sometimes they say things like “you don’t have to do this” or “Jesus loves you”. But people being harassed can recognise when they are being condemned whether the weapon is abuse or condescension.

And underlying the street theatre is the ever-present possibility of escalation to violence. Across the world, even here in Aotearoa, “pro-life” extremists have committed violent acts, including 11 homicides in the US.

Let’s be clear: anti-abortion harassment is not about changing people’s minds or “saving babies” – it’s about using the fear of violence to make people do what you want.

Anti-abortion folks sometimes defend their harassment by asserting they are trying to “help”, to “save them from future regret”. This is wrong on many levels. First, 99% of abortion patients believe they made the right decision, even five years later. Second, the harassment persuades very few people to change their plans, a fact acknowledged by some anti-abortion activists.

What about people who are conflicted or undecided? Does the presence of these anti-abortion activists provide them with help or information that they would not otherwise receive?

The answer in almost every case is “no”.

The folks who harass people outside abortion services often try to frame abortion providers as forcing people to have abortions. In reality, people who work in abortion services have no interest in providing abortions to anyone who does not want one. At some point the conflicted person will have the opportunity to tell someone at the service about their ambivalence, and be invited to go home and think some more. At the end of the day, section 11 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act recognises the right to refuse medical treatment.

What about free speech?

Rights and freedoms in New Zealand are subject to a balancing act. In this case, the rights of anti-abortion activists to freedom of expression and manifestation of their religion in public teaching are balanced against the right of pregnant people to privacy, and the right not to be discriminated against on the basis of sex and pregnancy. Fundamentally, it involves the right of people who are not public figures to be left alone.

The right of anti-abortion activists to express themselves is not being curtailed, it is being moved down the road no more than 150 metres. What is being curtailed is their ability to target people who are there to attend a medical appointment – which has nothing to do with them.

Freedom of expression has been exercised when you have said your piece. It does not include the right to pick your audience and make them listen by coming at them when they’re vulnerable and cannot escape. That is an abuse of freedom of expression.

Accessing safe, routine, legal health care is not a political act; it is a private act. Trying to dissuade people from doing so is not political speech; its purpose is not to argue for changes to the law, but to bully someone out of doing what they came there to do. Because the speech’s content is private, it should be treated no differently from other forms of verbal harassment.

As Dr Moana Jackson put it, “No one’s exercise of free speech should make another feel less free.”

Why can’t pregnant people just ignore the protesters?

Because that works so well with bullies. Except it doesn’t and never has.

It’s fascinating and maddening how the anti-abortion folks act like abortion patients are the ones acting outside acceptable norms by thinking they are entitled to walk into a doctor’s appointment without being verbally harassed.

Why do abortion patients have to be brave enough to face down bullies in order to get care? No one else has to.

Should people have to demonstrate personal courage and resilience in order to receive safe, legal abortion care? No. That should not be how we apportion medical care in New Zealand.

Putting the onus on pregnant people to deal with the harassment by pretending it is not happening perpetuates the stigma that has surrounded abortion for so many years. Eliminating that stigma was one of the reasons New Zealand amended the law last year to treat abortion as what it is – health care.

Why do they do this?

What could possibly motivate people to harass other people when it is clear how unwelcome their presence is? I believe the answer may lie in the historical works of Dame Margaret Sparrow on abortion in New Zealand.

A recurring theme in the stories she recounts is the hostile reaction of doctors and nurses to women who were injured receiving illegal, unsafe abortions. They were dismissive, unsympathetic, and downright cruel to women who were brought to hospital bleeding, in agony. They withheld pain meds, forced them to wait in chairs or on stretchers placed in public corridors, and repeatedly told them they had brought this upon themselves. They were meting out what punishment they could.

But today when a person receives abortion care they meet with kindness and professionalism. No punishment is forthcoming from the medical profession, or the justice system.

The only punishment for people getting abortion care in modern times is what they receive from anti-abortion harassment in the walk to the door.

I believe that impulse to punish is the motivating factor for most people who lie in wait for abortion patients. Else why would they still be doing it in the face of overwhelming evidence how their presence distresses the people they target?

This is not to discount another possible motivation – scaring providers away from offering abortion care in the community. Who wants a mob of screaming busybodies with gory signs outside their place of employment?

In a few weeks, anti-abortion forces will go along to the select committee considering the safe areas bill and tell it, “Oh no, anti-abortion violence only happens in other countries. New Zealand is different.” Alas, New Zealand is not different.

How many people have to be harassed, chased, assaulted for parliament to admit New Zealand exceptionalism is no defence against an ideology that believes people should be forced to bear children against their will, by any means necessary?

If parliament does not provide for safe areas, it will be making a value judgment that the right of anti-abortion activists to yell “murderer” and bully people out of accessing legal healthcare is more important than the right of patients to receive healthcare without harassment. It would not be the first time the human rights of a group primarily composed of women was made to give way to the “rights” of those who want to control and harm them.

Please tell your MP and your party of choice to support the safe areas bill.

Terry Bellamak is president of ALRANZ Abortion Rights Aotearoa.