Huge amounts of money are flowing through anti-vax and anti-mandate groups connected to the protest, and questions remain about where it all ended up.

This article was first published on RNZ and is republished with permission.

Police will not give details about finances and their investigation into the protest which occupied Parliament’s grounds and surrounding streets. Large sums of money traded hands during and leading up to the 23-day occupation, but it is unclear how the money was spent and who has benefitted.

Fight Against Conspiracy Theories (Fact) Aotearoa spokesperson Lee Gingold said groups like Voices For Freedom had been flexing their financial muscle.

“I think it’s a mistake to think they’re unsuccessful in their search for funding or that it’s too ramshackle because Voices For Freedom have splashed a lot of money around,” he said. “They funded the court case which led to the exemption for the police, which I believe was $90,000 and in Wellington … there are a number of billboards from Voices For Freedom up around town.”

Voices For Freedom is the trading name of TJB 2021 Limited. VFF founders Claire Deeks, Libby Jonson, and Alia Bland serve as its sole directors and shareholders.

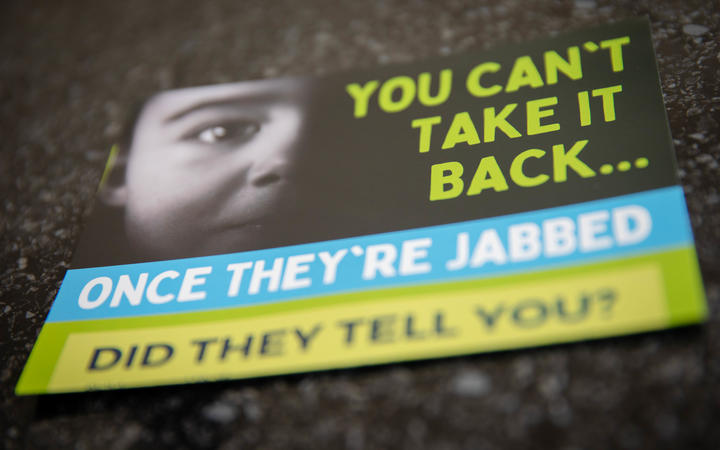

The anti-vax group has admitted they were behind the distribution of two million flyers, thousands of large rally signs seen at the parliament protest and other protests around the country, as well as billboards in Wellington, Auckland and Christchurch.

The billboard sites were managed by Jolly Billboards.

Its director, Jonathon Drumm, told RNZ he did not want to comment other than to say the company complied with all the rules of the Advertising Standards Authority.

Drumm said Voices For Freedom were “probably not” one of the company’s larger clients, but he would not comment on whether the group received any kind of discount compared to other customers.

Financial transparency of Voices For Freedom

On their website, Voices For Freedom claim they intend to be transparent about their finances.

“VFF is funded through individual donations from thousands of concerned Kiwis. Funding is put towards the various projects we facilitate and the general running costs and overheads of the organisation,” the website says.

“Like any well run organisation receiving funding we intend to provide basic information on finances such as to provide accountability and transparency at appropriate junctures and at least annually.”

However, no financial statements for the group are available online.

RNZ tried contacting co-founder Claire Deeks, who was third on the list for Billy Te Kahika and Jami-Lee Ross’ failed Advance New Zealand Party, but was unsuccessful.

Voices For Freedom did not respond to a set of questions sent to them regarding their finances and promises of transparency.

During a 2020 podcast on which Deeks was a guest, host Pete Evans pushed people to sign up as distributors of doTerra, a multi-level marketing company selling essential oils, for which Deeks was apparently a platinum-level “Wellness Advocate”.

Early in the pandemic, doTerra International was warned by the US Federal Trade Commission for social media posts made by reps claiming essential oils could prevent or treat Covid-19.

Fact’s Gingold said the groups involved in the protest and the movements surrounding it had a variety of motivations.

“I think an awful lot of it is a grift. I think of Billy TK quite early on in the pandemic asking for money in every single post. You have to question whether or not some of these people actually believe what they’re pushing or whether it’s just another thing for them to push,” he told RNZ.

“It’s pretty hard to know their motivation, but you do start to get a bit of a vibe for it. If someone is just asking for a lot of money and they’re prepared to flip-flop their views pretty easily then it feels like a grift to me.”

A protester from Whangārei told RNZ he had heard there were “big donations” for the occupation. “But I don’t really know what’s going on … I honestly don’t know where the money is going.”

The protester said he instead had concerns about government spending and the lack of transparency around that.

Detailed documents of the government’s budget are published every year.

Destiny Church and the Freedoms & Rights Coalition

The Freedoms & Rights Coalition, which was also involved in protests during the pandemic, did not respond to RNZ inquiries about their finances and donations.

Ashleigh Marshall, who is listed as the sole director and shareholder of The Freedoms & Rights Coalition Limited, worked as an administrator for Destiny Church.

Church spokesperson Anne Williamson said there was no relationship between the two. “Freedoms & Rights had a presence down at parliament virtually from day one, but there was no financial involvement that I know of. I can check this all up for you.

“And there certainly is no financial or other tie up with Freedoms & Rights and the church.”

She said any further questions should be emailed to the church. But there was no response to further inquiries.

Self-proclaimed Apostle Brian Tamaki had spoken at several events organised by the group and shared many of their posts on his personal social media in the past.

‘They robbed those Māori whānau’ – National Māori Authority chair

National Māori Authority chair Matthew Tukaki said such groups were taking advantage of disaffected New Zealanders, particularly Māori.

“They were targeting vulnerable Māori. Māori that are more predisposed because of our history, because of colonisation – some of our people are already down that bloody hole,” he said.

“What that group did, those leaders in that coalition, they robbed those Māori whānau not only of what little money they probably had, but also their mana.”

Tukaki said considering the precursor activities to the parliament protest, there was probably “about tens of thousands of dollars that had already been raised for that first stage”.

He said he suspected there was likely even more funding once the occupation began, with all sorts of supplies being provided on a daily basis.

“It might’ve been $10 from Mum here, $20 from old mate down the road, whatever the case, but to sustain the enterprise for those couple of weeks down in Wellington it would have required hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“For example, we know Wellington City Council was handing out parking fines for vehicles that were illegally parked. We know at its height the police estimated there were roughly 800 vehicles down there. If you do the maths … you’re getting up to a huge amount of money per day.

“What was happening is people were going into one of the tents, they were presenting people in that tent with those parking fines and those parking fines were being paid. So that tells me for just the tens of thousands of dollars per week for just parking fines, there was money ready to go.”

‘Where did the money come from?’

Some businesses had fronted up on their financial involvement, but Tukaki said he believed there was more to it than individual donations.

“We also know those attending were less likely to have oodles of savings and money in their pocket to sustain themselves for a long protest,” Tukaki said.

“So that comes down to where did the money come from? Well because we’ve got pretty lax laws in understanding money flow of overseas donations or overseas funds for these sorts of protests we are never going to actually know the true extent of what came in from overseas, but I would argue that a significant amount of money was being raised offshore.”

Social media posts among protesters speculated that some donations, potentially tens of thousands of dollars, had gone missing.

RNZ asked one of the protest’s organisers if she would comment on the situation.

She declined, but in a post to Facebook said: “The original [bank] account was someone’s who turned out couldn’t be trusted and him and another organiser for the north took that money.”

She wrote that she understood it was being investigated.

RNZ asked police whether any theft, fraud or financial crimes formed part of their investigation into the protest.

In a statement, a spokesperson said police were not in a position to comment on specific aspects of their investigation. “The investigation phase into the criminal activity during the operation is underway,” the spokesperson said.

“Police are appealing for the public’s help to identify anyone involved in criminal activity during the operation and anyone with information is urged to report it to police.”