As the number of New Zealand citizens deported from Australia grows, so too does the death toll. Don Rowe reports on the rising human costs of Australia’s immigration reforms.

This feature was made possible thanks to reader contributions via Spinoff Members. See here for more.

In June 2017, at the Anchor Baptist Church in Lower Hutt, Matthew Christopher Taylor was born again. Two days later he was dead, his body found in a Petone playground 2,000 kilometres from home.

A resident of Australia for more than 25 years, Matthew Taylor is one of almost 1500 New Zealand citizens deported since 2015 under a series of hardline and populist immigration reforms. The changes, which grant the Department of Home Affairs the power to deport foreigners on nebulous ‘good character’ grounds, have seen permanent, lifelong residents pulled from their homes and families for as little as associating with the wrong crowd.

“He was a product of Australia. He might have been a New Zealander by birth but he went to school there, his friends were there, his school is there,” cousin Justin Taylor says. “The Australian government are culpable. He should not have died here.”

As the number of deportees has mounted, so too has the death toll. In the past three years, at least four New Zealand citizens have died in Australian custody or immediately following deportation, and researchers believe there are almost certainly more. The New Zealand government has no estimate of the total number of deaths, and Minister of Justice Andrew Little says his office is powerless to force a change in Australian law. “We don’t have any control over what the Australians do. We don’t have a great deal of leverage.”

Advocates in both countries say Australia’s actions are in direct contravention of United Nations conventions against torture, and in several cases even children have been locked in isolation or detained with adults, forcing tense political standoffs.

More than 15,000 New Zealand citizens are expected to be deported in the next ten years; a flood of exiles, many with no connection to this country, never allowed to go home.

One afternoon in early 2016, Matthew Taylor stepped off the plane in Wellington. His cousin, Justin Taylor, waited anxiously in arrivals, scanning the crowd for a face he’d never seen in the flesh.

“I was sitting around, watching people go in and out, and after about half an hour a cop came over to me,” Justin says. “He said ‘your cousin has landed, but he’s been met by police and taken to be interviewed. We don’t know how long it will take.’”

The next morning, Justin took a train from central Wellington to meet Matthew at his probation service in Upper Hutt. Matthew was dressed in a baseball cap, hoodie, some jeans and a pair of Nike’s – his usual get-up.

“Before he left I’d told him the weather here was a lot colder,” Justin says, drawing on a cigarette. “But I think that’s also just how he liked to look.”

After processing at probation, the pair went to the pub. Matthew chucked $20 in a pokie machine, lost, and the two cousins spent the rest of the afternoon catching up over a couple of beers. There was a lot to talk about.

Matthew Taylor moved to Western Sydney with his father at the age of three. A blonde and wiry kid, he represented his primary school on the swim team, and later turned that passion for the water into skill as an angler. When Matthew was a teenager, his dad Glenn died of an overdose, and drugs would shadow Matthew too.

Matthew owned a supply business with four employees and loved the Kings of Leon and bourbon RTDs. His friends teased him for dressing like a lad, but he insisted it looked ‘too cool’ not to. On his neck was a tattoo of a silver fern, the closest he’d been to New Zealand in a long time: afraid of being denied reentry, he’d even missed his grandfather’s funeral. Matthew Taylor adored his son Jacob, his pride and joy, and liked to draw and write songs. Friend after friend points to his sense of humour. But he was human, and had his demons. Matthew’s life in Australia was marked with more than one run in with the law.

After serving a final six month sentence in 2015, Matthew learned the government wasn’t done with him yet. As a New Zealand citizen, he now fell foul of the Department of Homeland Affairs’ good character test, and would be deported. On release from prison Matthew entered the Villawood Detention Centre in Sydney, isolated from his young son and family but for a cellphone connection. His supply business collapsed almost immediately and Matthew’s four employees lost their jobs.

As he faced up to the reality of deportation, Matthew made contact with one of the only people he knew of in New Zealand, his cousin Justin. They struck up a relationship, and spoke regularly on the phone. One day the connection went dead.

“I didn’t hear from him for about 36 hours,” Justin says. “And it turned out it was because they’d taken his phone away from him. They took his phone and they moved him to a more secure and isolated facility, and they told him if he didn’t sign his deportation papers they’d send him to Christmas Island. Three weeks later he was here.”

That night Justin put Matthew on a bus for Karori, and two days later the pair travelled onwards to the family house in Whanganui, where Justin lives with his mum. For now, this was home.

There is no official count of immigration-related deaths in Australia. The only publicly available record is Monash University’s Australian Border Deaths Database, a horror list of more than 2000 drownings, beatings, and self-immolations stretching back almost 20 years.

Rebecca Powell, managing director at Monash’s Border Crossing Observatory, says her team of researchers comb media reports and a network of NGOs to locate and verify immigration-related deaths, but it’s an imperfect process made more difficult by the government’s distaste for transparency.

“The Australian government does not have anything like this particular list,” says Powell. “I assume they wouldn’t be interested in publishing one either, because one of our reasons for doing so is to hold the government accountable to some degree for these deaths.”

“I’d say we can safely draw a conclusion that there are other deaths that we’re just not even aware of.”

Nor does the Australian government provide New Zealand with any notice when a citizen dies in detention. Justice Minister Andrew Little says only repatriated bodies would be counted in any official stats. Those cremated or buried in Australia go unnoticed.

“Asking them to keep official records of causes of deaths and what have you, particularly in relation to New Zealanders, and to make those available to the New Zealand government – of course we should ask for that, but I don’t hold my breath about them being willing.”

While much of the international attention has been on Australia’s internment of refugees on islands in the Pacific, the treatment of New Zealand citizens takes the unusual step of applying brutal detention and deportation policies on a population long considered to be a close and trusted ally.

Section 501 of Australia’s Migration Act gives the Department of Home Affairs the power to cancel the visa of any non-citizen who fails a ‘good character test’. 501’s, as they become known, can be deported if they have been either sentenced cumulatively to 12 months in prison, or if they are deemed to have been ‘associated’ with a criminal group.

In the past year, more than 600 New Zealanders like Matthew Taylor have had their visa cancelled on character grounds alone. Many had spent their entire lives in Australia. Some had not stepped outside the country since childhood. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern says that while her government has emphasised that lack of connection, Australia are acting within the law.

“But ultimately there is still that question of whether it should be happening in the first place,” she says. “We raise it consistently, and will continue to do so.”

Examples documented by advocacy group Oz Kiwi include an elderly man buying medicinal marijuana for his terminally-ill wife, and an intellectually disabled youth detained for graffiti-ing a wall. Ko Rutene, a decorated former soldier and one-time bodyguard to John Key, was deported in 2016 for associating with the Rebels bikie gang. He had no criminal convictions or charges pending.

“What is happening I think is extraordinary abuse,” says Andrew Little. “You have a situation where somebody has done all their growing up in Australia, then offended criminally or associated with others or otherwise not met the various tests under Australian law – then to uproot someone from their community, from their household, and to put them in a country that is for all intents and purposes a foreign country to them, that is an extraordinary punishment.”

And before every deportation comes detention.

In late 2015, Junior Togatuki, a 23-year-old New Zealand citizen who had lived in Australia since age four, was held for up to a month in solitary confinement at a Sydney Supermax prison awaiting deportation. After his sentence for armed robbery lapsed, Togatuki’s visa was cancelled on good character grounds, and he entered the limbo of immigration detention.

Unlike Matthew Taylor, who entered the Villawood facility and thus had access to a cellphone, Togatuki soon learned he would continue to be held alone in maximum security. His psychiatrist noted an immediate increase in psychotic symptoms and upped his medication. One week later he was involved in an altercation with a corrections officer and was teargassed and forcibly restrained.

As his mental health worsened, Togatuki penned Immigration Minister Peter Dutton a desperate letter begging for amnesty.

“If I was to be deported back to New Zealand, I will be truly lost with myself,” he wrote. “I have no one there, no job, no home or a roof over my head. I’ll lose all I have. I’ll lose my family. I’ll lose hope in life if I go to New Zealand. I’ll break down completely.”

His pleas went unanswered.

Shortly after 9pm on September 11, Togatuki sent two calls for help over the prison intercom, telling guards he had harmed himself. No one responded. There was a big NRL game that evening. Sydney Roosters were playing, down two points in a final against the Melbourne Storm when the first call from Togatuki came through. One of the guards confirmed later that the TV was on – and Togatuki had a history of nuisance calls. By full time, blood and water were spilling from beneath his cell door. Junior had flooded his room, in what investigators speculated was a last attempt to get the attention of guards walking past.

He was unsuccessful. CCTV recorded four different guards walking through the puddle of Togatuki’s blood before morning came.

In the early hours of September 12, 2015, armed officers entered Togatuki’s cell and pinned his stiff, rigored body beneath a riot shield. On the walls were messages written in blood.

“God forgive me,” one read. “I’m sorry.”

A coroner’s report found there was a window of at least five hours in which a simple medical intervention would have saved Junior’s life. All in all, it would be 11 hours from that first call for help until his body was discovered.

Unlike almost every democracy in the world, Australia has no human rights charter, and thus their many immigration detention centres are closed to United Nations inspectors. But Professor Gillian Trigg, president of the Australian Human Rights Commission from 2012-2017, says on her regular visits she found the centres ‘appalling’.

“I would describe the conditions in Blaxland facility in Villawood prison as in breach of the United Nations torture convention,” she says. “My personal view is that these facilities are designed to break people. At one level it’s torture and at the other it’s spitefulness.”

“Conditions were quite simply the worst I’ve ever seen,” she continues. “They were simply dreadful. And even the guards and supervisors that were with me were saying they were pretty ashamed of it and that they were hoping for new buildings to be created.”

But Australia’s Migration Act provides little guidance regarding the management of immigration detention centres and so facilities like Villawood, where Matthew Taylor was held, are managed by contractors – in this case controversial private security giant Serco.

Trigg describes seeing six men to a room, 20 in total, in a facility the size of a suburban home – albeit one surrounded by 14 foot steel fences.

“They are in appalling conditions with nothing to do, absolutely nothing to do except to watch the television. And some of them are mentally ill in my view, or certainly deeply disturbed.”

Doctors and advocates have recorded multiple instances of chronic self harm and suicide attempts in the facilities where New Zealanders await deportation.

Conditions at Maribyrnong, where researchers at Monash University believe another unidentified New Zealander was found dead in March, 2017, are notoriously severe.

“Maribyrnong detention centre is known for its brutality and for its complete hostility towards detainees,” says Filipa Payne, New Zealand-based founder of advocacy group Iwi n Aus.

“While I was there I visited people that I had met before in other detention centres, and I can tell you that every single person that I saw in Melbourne, their mental health was deteriorating rapidly.”

In another case in Western Australia, a 17-year-old New Zealand citizen was held in the notorious Intensive Support Unit at youth facility Banksia Hill for more than 300 days after a riot squad shut down a ‘disturbance’. Advocates say the boy, who remains at the facility, began to self harm, and has asked his family to stop visiting due to embarrassment. His mum describes him as defeated. He will be deported upon release, despite having moved to Australia when he was 10.

The callous treatment of detainees extends to their families, too. In April, 2016, New Zealand citizen Robert Peihopa was found dead after a fight in a CCTV blindspot at Villawood’s Blaxland compound. The coroner ruled he had suffered a fatal heart attack likely triggered by emotional and physical distress, and his use of methamphetamine earlier that day. Peihopa, 42, had lived in Australia since he was 15. He had four children and died alone in detention almost a year after serving out his prison sentence. Neither the Australian authorities nor Serco called his family on the day Robert died. Hera Peihopa, Robert’s mother, first learned of her son’s death via text messages from other detainees. She says Serco “doesn’t give a damn” about the men under their control, and had put her son under the supervision of inadequately trained staff.

“Since Robert’s death not one person from Serco or the Department [of Home Affairs] has called me or spoken to me or written to me to say they were sorry about Robert dying on their watch. My son was dead inside Villawood and all I got – all my family got – was arrogant indifference shown by Serco officers and the department.”

As of June this year, there are 173 New Zealand citizens in immigration detention in Australia. It was from these detention centres that Matthew arrived in New Zealand, determined to appeal his deportation and return to his family and son in Australia.

Just before Christmas, 2016, Matthew Taylor vanished.

Having moved from his aunty’s home into a relative’s place over the back fence, the seduction of old habits in a small town had proved too much to resist. He was in trouble, using drugs and spending time with gang members. Family suspected he might be depressed. Matthew made a break for it.

“He changed his cellphone, blocked everyone on Facebook, just disappeared,” says Justin. “I heard through my cousin that he was having a few problems, but we had no way of contacting him. My mum wanted him to come back to Whanganui but we had no way of getting in touch. That was the last we saw of him.”

Matthew went south and got a job in Petone repairing gutters. He found a flat on Waione Street, just across from the Esplanade, and withdrew into himself. Matthew’s mum was sick and his girlfriend, at one time considering a move to New Zealand, had broken off the relationship. Desperate to get home, he’d lodged an appeal with the Department of Home Affairs. All he could do was wait.

Akshay Samuel, an engineering student at Weltec, moved in soon after and says he felt immediately drawn to Matthew, who appeared isolated in the household of eight.

“He was a very sincere guy, he seemed very honest, but nobody was talking to him,” says Samuel. “So I said ‘hey bro, what’s your name, how’re you doing’ and from there we became friends.”

The pair started to cook for one another and ate together on newspaper on the floor. Akshay had never heard of bolognese. It was Matthew’s first experience with an authentic egg curry. Akshay found Matthew more open than most New Zealanders he had tried to befriend, and in turn became something of a confidant.

“I told him my story and eventually he told me his.”

Matthew’s life in New Zealand was beginning to spiral. In early April he was involved in a car accident and fractured his clavicle. The crash wrote off the work van and Matthew lost his job. Police visited the house; they wanted to speak to him about a fraud case. By May he was taking medication for anxiety and depression. Police visited again, bringing charges of careless driving and blackmail. And still he waited for word from Australia.

“That was his only goal,” Akshay says. “He was saving money to see his mum, he wanted to go back to Australia – but he could never get a visa. And so he was waiting and waiting to find out if he could go back.”

Matthew’s GP recommended he see WINZ for counselling. Instead, after an invitation from Akshay, he turned to the church. The pair went shopping for a new dress shirt and made their way to the Anchor Baptist Church, a squat building more akin to a school hall than a cathedral.

Reverend Bobby Nato says Matthew struck him as shy and reserved.

“He was a very quiet boy. I couldn’t really tell what is inside his mind, but his demeanour was very quiet. The first time I saw a smile on his face it was quite extraordinary.”

“But he had nobody here in New Zealand. If Matthew had never been deported,” he trails off. “He was a young boy. It was so early in his life.”

At the start of June, Matthew received a letter from Home Affairs. His appeal had been denied, and he would never be allowed to go home.

Whereas Australians in New Zealand enjoy almost equal status, New Zealanders in Australia are denied access to everything from social services to student loans. New Zealand citizens are unable to claim compensation for abuse suffered while in Australian state care or custody. All those privileges are reserved for citizens – and since 2001, less than 10% of New Zealanders who settle in Australia have taken out citizenship. Māori and Pacific Island citizenship rates are less than 3%.

Without the protections of citizenship, migrants are in a precarious situation. And every time a New Zealand citizen is detained, the effects flow outwards. There’s a mourning period in the home, Payne says, and children stop going to school.

“They then also become anti-establishment and fearful, and they fear reaching out to be helped in any process because of what the outcomes might be for them.”

Apathy towards the system also means Kiwis in Australia lack any political mechanism by which to change their situation, Andrew Little says.

“Even though there’s 650,000 odd New Zealanders in Australia, most of them aren’t entitled to vote, so you can’t even go that route.”

And according to many Australian politicians, that’s just as it should be.

“The general sentiment that’s expressed to me is that ‘this is our law, we’re doing it for good reason, we want to protect the good name of Australia, we make no apology for what we’re doing’,” says Little. “They typically characterise the people in immigration detention as unworthy, and therefore there’s little remorse or contrition.”

Indeed, Peter Dutton – the polarising former immigration minister who dramatically failed in his bid for the prime ministership in August – has expressed frustration at not having even greater powers like the ability to deport New Zealanders who hold dual citizenship, calling it ‘a deficiency in the law.’

“This issue is definitely putting a strain on the relationship, as it should be,” Andrew Little says. “No citizen from any country should be treated this way. If there are more cases of deportees coming to New Zealand, struggling, and facing the kind of trauma and tragedies that we’ve seen, if that continues, then I would certainly hope at some point there will be somebody there, official or politician, who is prepared to pipe up.”

The Australian Department of Home Affairs has not responded to a request for comment.

Justin Taylor was having a morning bath when the police arrived. Two shadows moved past the window and there was a sharp bang on the door: “one of those ones where you just know it’s the police.”

“My mum called out and said the police were here. I just knew it was Matt. I thought, ‘yep, he’s done it.’”

“There’s a lot of guilt. You always wonder if you could have done more, if we could have spent more time with him. But life has to continue. It’s tough.”

“I think the Australian government are culpable. They need to take responsibility for what they’re doing to people, what they’re doing to families. Unless policies change these tragedies will keep occurring”

Akshay Samuel keeps a picture of Matthew in an old bible. He remembers him as gentle and kind.

“The day before he died I sent him a text, it’s the last text on his mobile, and it just says John 3:16,” says Akshay. “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

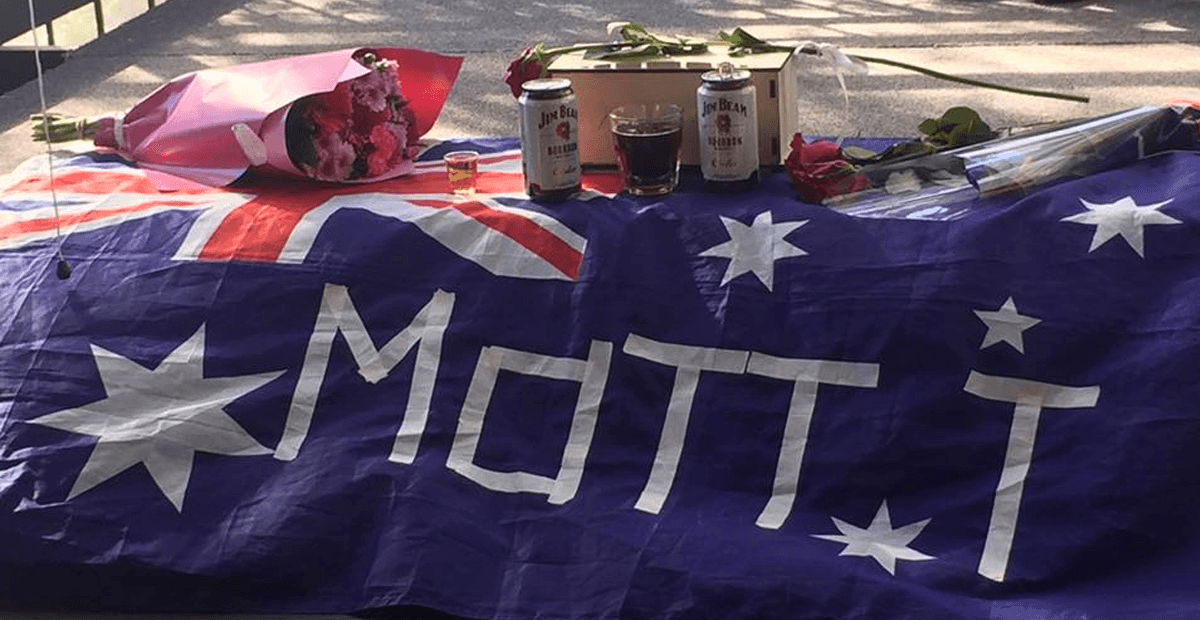

Matthew’s body was returned to Australia after friends raised more than $2000. Following a service at Penrith’s St Nicholas Church, Matthew was buried beneath an Australian flag. He was finally back home.

This feature was made possible thanks to reader contributions via Spinoff Members. See here for more.