Today marks one year since the catastrophic floods in which four people died, many lost their homes, and the infrastructure of the city was broken. How has the city changed since then?

When the heaviest rainfall ever recorded in Tāmaki Makaurau crashed down on January 27 2023, the city was woefully unprepared. Roads turned to rivers, parks turned to lakes, cars were washed away and water rushed into homes. People were confused and terrified. Official communication channels were silent, and instead TikTok informed people as the rain pounded down. Slips cut residents off in Muriwai, Piha and Karekare. The airport flooded, trapping thousands of people inside. People walked for hours in the rain because there was no other way. Four people died, and emergency rescue staff were pushed to breaking point. It was carnage. Then barely three weeks later, Cyclone Gabrielle arrived.

“The Auckland Anniversary Floods were an important wake-up call,” said mayor Wayne Brown in a statement on Friday, implying the sleep that comes before waking. He says he’s proud of the “long overdue” work done across council groups since. The immediate emergency response by officials has been much criticised, as being too slow and inadequate. Now that’s over and we’re in the recovery phase. Experts have reviewed, money has been allocated, and a year has passed, so how is the city doing now?

Auckland Transport is building back better

Auckland’s deadly deluge highlighted how unprepared the city is for extreme weather, as its transport network was stretched to its limits. Public transport routes were closed or detoured, and cars that weren’t underwater were stuck in absurd traffic. For example, a normally 20-minute drive from Mount Smart stadium to Newmarket took more than three hours. Following the floods, millions of dollars worth of repairs were necessary to fix the city’s transport infrastructure, and some are still ongoing.

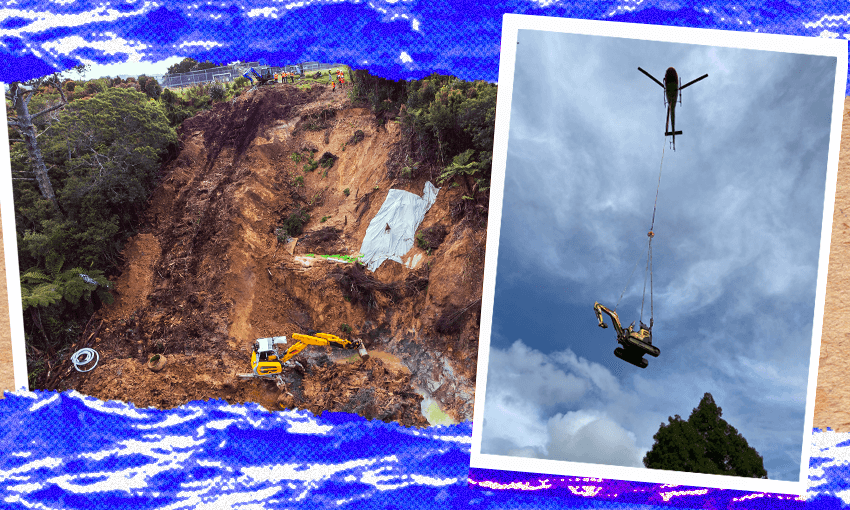

Auckland Transport’s infrastructure and place director Murray Burt explains that AT is still recovering from the floods which, alongside Cyclone Gabrielle, caused 2000+ issues. One year on, “we’ve made some good progress on fixing over 75% of these sites,” he says,” but there’s a lot left to do.” That includes 430 road repairs still to go. While Burt says they’re trying to minimise disruption, he admits that some repairs “are very complex, and it won’t be until the end of 2025 before most of these are complete.”

Alongside their extensive repair programme, AT has also made essential routes more resilient. Burt explains: “Though our flood repair programme is focused on recovery, we are taking the opportunity to build back better where we can.” One example is North Shore’s Glenvar Road, which “required an extensive rebuild, and now has improved pedestrian safety and a much stronger road foundation that will allow it to last into the future.”

As well as rebuilding infrastructure, AT has updated its protocols for emergency situations. The floods necessitated faster, more reliable and more consistently accurate real-time transport service information, which has continued since. As well as collecting practical experience and data to inform responses to future extreme weather, staff gained experience in improving contingency planning across Auckland’s transport network – for example, proactively monitoring vulnerable areas.

Armed with lessons from the Anniversary Weekend floods, AT is confident it can provide better guidance to operators and customers in the future. The experience also holds warnings for transport organisations across the country. Responding to extreme weather “is not a challenge exclusive to Auckland,” Burt says. “Many parts of the country will need more resilient infrastructure ahead of further weather events. There is a lot of work to do nationwide.”

Temporary repairs are holding together the water and wastewater networks

After last summer’s storms there were more than 200 issues, many due to landslips, affecting Auckland’s water and wastewater networks. Many weren’t immediately apparent – new damage reports came in for months. The recovery programme is ongoing. While at least 60 issues have been resolved, many other repairs are underway – for example at the water treatment plant in Pukekohe, which is still out of service.

Initial emergency repairs and bypasses have been replaced with temporary solutions that are expected to last “a couple of years”, says Suzanne Lucas, Watercare asset upgrades and renewals general manager. The temporary solutions allow time for thorough planning and design, ensuring the eventual permanent solutions will be fit for a future with more intense weather events.

Ironically enough, Lucas says one of the biggest challenges to fixing the water networks has been the weather. At many sites work had to stop immediately when rainfall safety thresholds are exceeded, and 2023 turned out to be Auckland’s wettest year on record.

The estimated cost of Watercare’s flood recovery programme is $100 million. More than $20 million has already been spent, and the rest is expected to be spent in the next two years.

There’s a new first consideration in the real estate market

“Did it flood?” is the first question buyers ask real estate agent Ben Buchanan at Harcourts open homes. If it did, the next question is about insurance. If it didn’t, some home buyers will ask if it’s in the flood zone. But many prospective buyers know all this already – they’ve learned to read LIM reports and are checking the council’s new tool, Flood Viewer.

If the house is no longer insurable, it will be “extremely hard to sell” because people will not be able to get finance, Buchanan says. And even if it is, fewer buyers are interested in flood-prone properties, all of which affects the method of sale (auctions are out since there wouldn’t be much, if any, bidding) and ultimately the price. Buchanan has seen prices hundreds of thousands of dollars less than they might otherwise have been.

He thinks with time and infrastructure upgrades the worries around flooding will ease, but at the moment, “it is a very hot topic.” Still, not all flooding risks can be mitigated by infrastructure, and consents are still being approved in floodplains.

Insurers are adapting to a new reality

In the wake of last year’s floods, When the Facts Change host Bernard Hickey spoke to Massey University banking and insurance expert Dr Micheal Naylor. They discussed how climate change-induced extreme weather events will affect property insurance. “One in four homes in Auckland are subject to flood damage, so it’s not a small matter,” explained Naylor.

Hickey said that after the floods, “House by house, street by street, drain by drain”, insurers will recalculate premiums. They’ll be “adapting their models, adapting their maps to account for the rising temperature and the rising extremity and frequency of events,” he added. The reason that insurers are adapting their flood maps from the council’s general floodplain maps to a property-specific model is because the floods proved historical floodplain data to be irrelevant. “If you look at the properties which were flooded in Auckland, a number have not been affected in the past,” said Naylor.

Because of those adapted maps and recalculated premiums, Naylor explained, “we’re facing a future where properties will have huge increases in premiums or become uninsurable” while homeowners are still expected to pay their mortgages. The insurance expert estimated that recalculated premiums will rise by four, five or even 10 times the original figure. Some properties will be categorised as so high risk that they will become uninsurable. Naylor said he’s concerned that once recalculations are completed, whole areas will become uninsurable.

Another warning from Naylor: some homeowners whose properties are still insurable, but only with increased premiums, will forgo insurance, asking instead for direct government compensation when disaster strikes. “If it’s a few people, that’s fine, but if it becomes one-fourth of the population [the amount of Aucklanders with flood-risk properties], the government simply can’t do it; there is no money.” Naylor warned. “My fear is that this will turn into an insurance crisis, then a banking crisis into a government debt crisis.”

West Wave pools are open again

The West Wave pools in Henderson had 250,000 litres of brown river water poured into them over the course of the floods. It took four days to pump it all out, and four months later, The Spinoff reported that NZ’s biggest swimming complex was mostly out of action. The lap pool, dive pool and learn to swim pool opened several weeks after the floods, but the more exciting leisure (aka wave) pool, hydroslides and spas and saunas didn’t reopen until October 9.

Repairs were complex since “everything got fried”, says Sarah Clarke, the facility’s manager. The council has replaced the entire electrical wiring and heating systems, and completed maintenance and seismic strengthening work. Impressive.

The city is spongier

In July last year, The Spinoff’s Shanti Mathias reported that a spongier city was rising from the aftermath of the floods. Sponge cities provide the opposite of impermeable tarmac roads and concrete footpaths that channel water through cities into enormous storm drains, and wipe out roads and houses when those storm drains fill. Instead, they work with natural systems to absorb water into soil, refilling groundwater supplies instead of depleting them. New designs for the city’s infrastructure include more porous elements like rain gardens and tree pits to help with stormwater management.

Parks and reserves are still waiting for fixes

After the floods and Cyclone Gabrielle the council was faced with 1,459 parks and community facility repair projects. Of those, 64% have been completed.

On January 4, RNZ reported that on the North Shore, four reserves are still completely closed, and 30 tracks are fully or partially closed. Members of conservation groups are worried that boardwalks installed to protect against kauri dieback won’t ever be repaired or replaced given the current tightening of purse strings.

Out west, the Arataki Visitor Centre reopened on December 2, and while many tracks have reopened, eight are so damaged they will be out of action “for some time”, with three awaiting “further investigation”.

Auckland Council says it’s more prepared for emergencies

Reviews last year found that Auckland Council’s emergency response was slow and inadequate. Much has been said about mayor Wayne Brown being missing at key moments, but the failure was system wide, not the fault of a single person. In short, Auckland Council’s emergency management system and leaders were “not prepared for an event of this magnitude and speed”, according to the first official review.

Adam Maggs, head of capability and strategy at Auckland Emergency Management (AEM), told The Spinoff “we have learned an awful lot in that time since then, about how we can prepare better, and be better prepared to respond more effectively moving forward”.

A key strategy document, the Civil Defence and Emergency Management Group plan, has been reviewed and is now with the minister of emergency management to be approved. This lays out the guiding principles for dealing with emergencies – reduction, readiness, response, recovery – and outlines actions within each. It describes the management and governance systems, monitoring and evaluation, and the hazards Auckland faces.

On the ground, the department has been restructured, adding 10 more roles. They include people who work specifically with each of the 21 local boards to develop readiness and response plans specific to their area’s hazards, demographics and facilities. “That will be instrumental,” says Maggs. Similarly, they are building relationships with 19 iwi, so that they can “supplement what [the iwi are] already doing”.

Also new is a severe weather standard operating procedure, which AEM didn’t have before. It sets out thresholds for weather and a plan of what to do when weather reaches them. Capacity has been increased to monitor weather and water levels live 24/7. “There’s always eyes looking” so when they hit thresholds, “it creates a trigger for us to be able to respond.”

After much criticism of the absence of Mayor Brown during the floods, Auckland Council has developed standard operating procedures for key roles, “so that they know exactly what they need to do, what their responsibilities are, and what they need to report on and take action on.” Similar guides have been made for elected officials and the mayor, so they know the role they are expected to play in an emergency. “That was something that we didn’t have prior to the storm events,” says Maggs. AEM has recruited a senior communications role to ensure internal communications go smoothly in emergencies.

AEM has also been training staff within council and partner organisations – 700 have had response training, and in October last year they carried out a multi-agency exercise to test readiness to respond to a similar storm event.

Another change we can expect to see is a revamped AEM website.

Climate change and resilience did not become a dominant election issue

Even though many commentators thought the floods and Cyclone Gabrielle would put climate change on the election agenda, polls showed that what people were mostly concerned about was cost of living, the economy, healthcare and crime. In one survey only 8% said they were concerned about the environment.

“Climate-based risk and infrastructure investment hardly raised a ripple in the various election debates of 2023,” says John Tookey, professor at the school of future environments at AUT. “Irrespective of political perspective there is an absolute need to prioritise infrastructural investments. Failure to do so will inhibit future growth and housing provision, impact cost effectiveness, as well as compromise the sustainability of our current communities.”

We are not managing a retreat

Since the floods 1,415 new house consents have been granted on Auckland flood plains. That’s about 10% of the total consents.

That’s also the opposite of what community-led organisation West Auckland is Flooding (WAIF) is calling for. They want managed retreat – the purposeful and planned movement of people out of the worst-affected areas, and building away from risks. The group, made up of flood-affected Westies, say that last summer’s event wasn’t the first major flood in West Auckland and it certainly won’t be the last. They argue that because the council consented to building homes in areas that flood, it has an obligation to find solutions that don’t put people at risk, and don’t take years to action. In other words, the council should buy people out and stop consenting in at-risk areas.

The council and government have yet to make a plan for relocations to reduce risk, says Ilan Noy, an expert in the economics of disasters and climate change at Victoria University of Wellington. The current arrangement “seems to incentivise more poorly-planned developments and investments in high-risk areas, and a refusal to recognise that the risks are changing because of climate change.”

“Nothing has been done,” he says. “It seems that when another inevitable disaster will happen, we will again improvise a response that will again fail to deal with the underlying risk from climate change.”

Roads out west are patched up, but not improved

Te Henga Bethells Beach community didn’t suffer too much from the Auckland anniversary deluge, but it did water-log everything. And then “Gabrielle came in and really smashed us,” says Scott Hindman, resident and chair of the local emergency resilience group. Roads were flooded, washed out and slipped away. The power went out. Today, things are far from fixed. Some parts of Bethells Road and Te Henga Road are still down to one lane, and there’s a whole car park and walking paths Hindman describes as “completely gone”.

“So far, the few repairs that they have done are just patching up what’s broken – they’re not doing anything to stop it happening again, or to make the road stronger. You can already see other bits of the road that will slip away next,” he says. “It’s almost like we’re still in emergency mode.”

The Domain lake is gone

Covered up, filled in and rerouted historic waterways across Auckland resurfaced during the floods, including the lake in Pukekawa/Auckland Domain. It was the first time this lake had reappeared since settlers filled it in during the 1860s. When the lake resurfaced, birds and dogs flocked to bathe in it, and people risked their health to kayak, kite surf and paddle board in the water. The lake, which covered much of the Domain’s sports field area, held so much water that it lessened flooding on other properties. Pukekawa successfully siphoned floodwaters away from neighbouring properties because its flooded section (the southwest corner adjacent to Carlton Gore and Park Road) was historically a volcanic crater lake into which runoff naturally funnels.

The lake dried up by March, but not for good. Throughout 2023, when Auckland experienced abnormally high rainfall, the lake resurfaced on several occasions. In fact, the lake didn’t dry up fully until October 2023, nine months after Auckland anniversary weekend. While we might not be able to see it right now, the lake is lying in wait till the next deluge when it can reappear as a novel inner-city water feature once again.

157 red and 935 yellow placards are still in place

In the aftermath of the floods, 5,455 white, yellow or red stickers were placed on houses that were deemed to have immediate risks. Almost 3,000 were red or yellow, meaning those homes had restricted or prohibited access. A year on, 157 red and 935 yellow placards remain in place; red meaning they are uninhabitable, and yellow meaning partially uninhabitable.

More than a thousand people are waiting for their damaged homes to be categorised

“It can never be enough. We can never go fast enough. And we never get things done quickly enough. You know, every extra day that passes for somebody who can’t live in their home, which is beyond repair, is a day too long,” says Mat Tuker, the head of the council’s Tāmaki Makaurau Flood Recovery Office.

Categorisation is the first step to getting a buy-out or other support. More than 2,400 properties have been signed up for assessment. Unfortunately, risk categorisation is a complicated process that takes time and specifically trained professionals, of which there aren’t many. “We expect to have got through most of [the assessments] by mid this year,” says Tuker. In the meantime, many homeowners are struggling.

Lyall Carter, chair of WAIF, says that “while on one hand, we totally get it, it’s still really frustrating for those that are caught in the middle”. He says most of the people he’s spoken to in West Auckland with damaged homes are first home buyers and young families who are being hard hit financially; some have to pay both mortgage and rent. “We have people that are running out of money,” he says. “Even after all of this process, there are going to be people that are left in a really bad financial state.”

Four homes have been bought out

Before Christmas, four buy-out settlements were completed. Properties must be designated as risk category 3, meaning they have an intolerable risk to life which cannot be reduced, to be eligible for a buy-out.

Another 60 property owners are actively working towards buy-outs and the council expects to buy out about 600 homes all up. Another 100 properties are expected to be category 2P, meaning they will receive financial support to make their homes safe, through fixes such as lifting homes and creating overland water flow paths.

The first relocations and deconstructions are scheduled for March. “Nobody wants empty boarded up houses next to them in their community. It’s not a nice thing, aesthetically, and it’s actually a safety risk as well,” says Tuker. As much as possible of their materials will be saved, reused and recycled. Then the community will be consulted on how they want the land used – it could be a community garden, playground, or something else.

People are struggling with their mental health

For many, the floods and their aftermath have been “harrowing” says Carter of WAIF. He says the group has had a number of reports that children and young people are struggling with their mental health, particularly with PTSD. “This is going to have a lasting impact.”

He says that while some parts of Auckland have all but forgotten the flooding, “we have streets that are empty, that were once filled with the laughter of children. Now they are overgrown and rat infested and constantly being looted. So it continues to be a living disaster.”

Communities have banded together

“I think one of the things that has come out from this is community, grassroots-led advocacy, like WAIF, and a number of other advocacy groups around Auckland,” says Carter. He thinks the groups have shown the power of democratic participation and community and wants to see more community-led organisations that look after each other, no matter who is in government. “I’ve been involved in community work most of my adult life, and this has been the best thing that I’ve ever done,” he says.

We should be getting ready for more

“If our habits don’t change, we will see wetter and wetter extreme rainfalls around the country, and heavy rainfalls will happen more often,” says James Renwick, professor of physical geography at Victoria University of Wellington. “I hope the lessons are not being forgotten and that we can all become more resilient and more prepared to deal with extreme rainfalls in future. Because they will come.”

But not this weekend. This week, MetService and Auckland Emergency Management have been keeping an eye on a cyclone forming in the Coral Sea. MetService has now said it’s not going to hit New Zealand at all, says Maggs. “Auckland is going to have a nice weekend.” The forecast, though, is rainy.