Once so abundant they darkened the skies, kererū are now struggling to survive. Dr Madeline Shelling (Ngāti Porou) argues it’s time to rethink our conservation model – and consider restoring tikanga-based harvesting to help save the bird.

Prior to colonisation, native birds ruled the land of the long white cloud. Aotearoa was cloaked in dense, abundant forests, teeming with manu. Joseph Banks, the botanist aboard the Endeavour, even wrote the following in a diary entry dated January 1770, as they were parked offshore from Tōtaranui (Queen Charlotte Sound), Marlborough Sounds: “This morn I was awakd by the singing of the birds ashore from whence we are distant not a quarter of a mile, the numbers of them were certainly very great.” But that’s just one man’s diary of a first encounter. It’s a drop in the ocean compared to the vast mātauranga Māori and deep scientific ecological knowledge developed over hundreds of years of a sacred, symbiotic relationship.

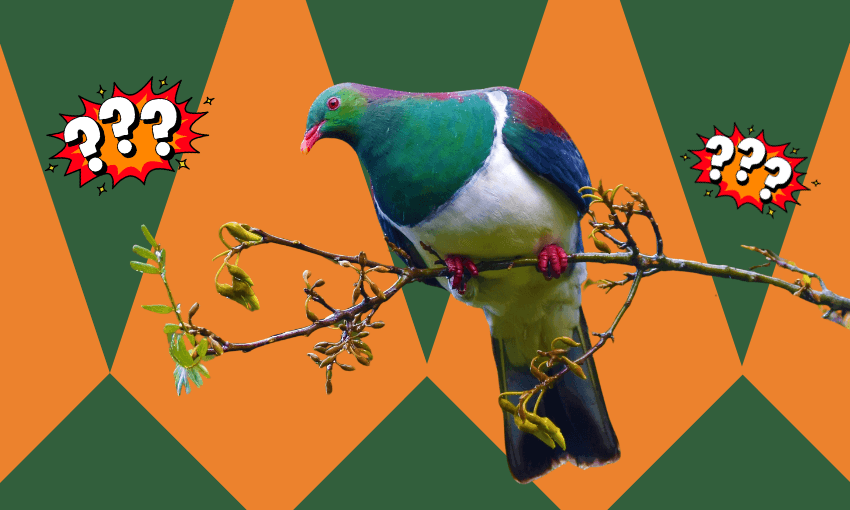

Kererū, also known as kūkū or kūkupa in Te Tai Tokerau, are an essential part of our forest ecosystem. With a slightly larger cousin on Rēkohu/Wharekauri (Chatham Island) called parea, these birds are the primary distributor of at least 11 of our biggest forest tree species; including karaka, miro, tawa, pūriri, and taraire. Deforestation and pest introduction have been the biggest drivers of their rapid decline since European arrival. They produce only one offspring per breeding season, and only breed on good fruiting seasons, making them even more vulnerable. While there are some success stories over decades of well-meaning efforts, kererū repopulation outside of pest-free sanctuaries is not fast enough to overcome predation and competition from cats, stoats, rats, possums and even myna birds.

Once so plentiful they could block out the sun as they flocked in their hundreds, the protection of kererū requires a radical transformation. If they die out, our forest will forever struggle to regenerate itself.

My solution? A carefully managed kererū repopulation programme that flips conventional conservation on its head. My goal is that through this programme, kererū once again become so abundant that it is no longer controversial to eat them.

Phase one: Establish or partner with secure breeding facilities, large aviaries or pest-free sanctuaries dedicated to kererū reproduction.

Phase two: Focus entirely on population recovery. Every single bird produced would be dedicated to boosting wild populations in predator-proof areas. Tree planting and pest eradication efforts will ramp up across the motu.

Phase three: Once healthy population targets are met, introduce tightly regulated, tikanga-based quota systems allowing 1–2% of kererū to be harvested for ceremonial and customary use.

Why eating kererū could save them

Kererū were, and sometimes still are, a highly prized food source. By the 1860s, laws began to control hunting activities. From 1864, hunting seasons were set in certain areas for kererū and native ducks. In 1865, The Protection of Certain Animals Act prohibited using snares and traps to catch native birds – meaning that shooting became the only approved form of hunting. This restricted traditional methods that had ensured an ongoing food supply for whānau, but allowed Pākehā to continue hunting kererū as game. Disputes over the hunting season ensued, as Māori preferred late autumn and winter when the birds were fatter, while Pākehā preferred early autumn, when the birds were more agile, adding to the “sport”. The law was repealed in 1866 but reinstated in 1907, when all hunting of native birds was outlawed.

However, the reduction of the kererū population is not due to traditional harvesting, but the drastically destructive changes to their environment. Deforestation has stripped away the ancient forests that once provided abundant food and shelter. Introduced pests have decimated their numbers by preying on eggs and chicks, while also competing for food. These combined pressures have driven kererū populations into decline, despite hunting bans and conservation efforts.

This raises a critical question: if the greatest threats to kererū are habitat loss and invasive species, where are our current conservation approaches falling short? Could a return to traditional practices – including consumption – be the key to saving them?

Consumption as conservation

Western conservation models are rooted in colonial ideas of European superiority, which promote “preservationism” – building fences and restricting human activity. While effective in some contexts, this approach contradicts Indigenous active management strategies and undermines the rights and knowledge of Indigenous peoples, who have managed their lands sustainably for generations. As put by Catherine Delahunty: “Pākehā environmental thinking is stuck in preservationism, as if the natural world was a museum or a magical depopulated Narnia where the plants and animals are waiting for the white ecologist rescuers to come and save them from evil.” On the other hand, indigenous management works in reciprocity with nature, emphasising stewardship, sustainable use, and co-existence – maintaining ecosystem health through active, place-based practices.

Māori enactment of kaitiakitanga is not just for environmental and food security reasons – it also represents revitalisation of important cultural activities, allowing for the continuation and transmission of mātauranga Maori. In Tūhoe, generations have relied on a range of qualitative indicators, including visual (e.g. decreasing flock size), audible (e.g. less noise from kererū in the forest canopy), and harvest-related (e.g. steep decline in harvests since the 1950) indicators to monitor kererū abundance and condition in Te Urewera. They have consistently demonstrated that autonomy is vital, highlighting that the ability to make management decisions according to mātauranga is likely to yield more effective and sustainable outcomes, both ecologically and culturally. Mātauranga like this should guide transformational restoration efforts.

However, Māori-led active management embedded in mātauranga and kaitiakitanga is a constant battle for recognition and meaningful integration in the conservation ideology of Aotearoa. This is certainly the case in Aotearoa, where Māori sovereignty and Te Tiriti-guaranteed rights to manage their own taonga species is often denied even at the highest level of government. While hunting kererū is illegal under the Wildlife Act 1953, te Tiriti o Waitangi guarantees full and undisturbed possession of taonga to Māori, which includes rights to harvesting. Hapū retain the right to enact kaitiakitanga, rangatiratanga and the responsibility to establish tikanga pertaining to the harvesting of kererū.

Len Gillman, a biogeographer at Auckland University of Technology, also argues that sustainable harvesting of kererū could satisfy everyone’s needs. Gillman suggests that careful management, including sustainable harvesting quotas based on kererū numbers and age distributions, holds great promise. Sustainable harvests would require robust monitoring and adaptive management, ensuring only surplus birds are taken and young birds have the opportunity to learn survival skills from older individuals.

A kererū breeding programme with the end goal of reclaiming harvesting traditions would challenge preservationist ideals. However, it could strike the balance between conservation and Māori rights better than the Wildlife Act ever could. Active management based on tikanga, such as controlled harvests, quota systems, and qualitative environmental monitoring informed by mātauranga, can improve species resilience and restore ecological balance. The real question isn’t whether we should eat kererū, but whether we can afford not to try radical solutions, because sometimes, saving a species might just mean putting it back on the menu.