Claire Mabey attended some of the 2025 Library and Information Association of New Zealand (LIANZA) conference and came away worried about school libraries, and creeped out by the bots.

Futurist Melissa Clark-Reynolds has AI’d herself. She’s created a digital double to do things like talk to the bank. “What if it starts talking to the bank’s AI and starts to hallucinate?” she posed to the 400-strong crowd of librarians and information experts. “It was scary,” she said, “how easily the AI got through various security systems.”

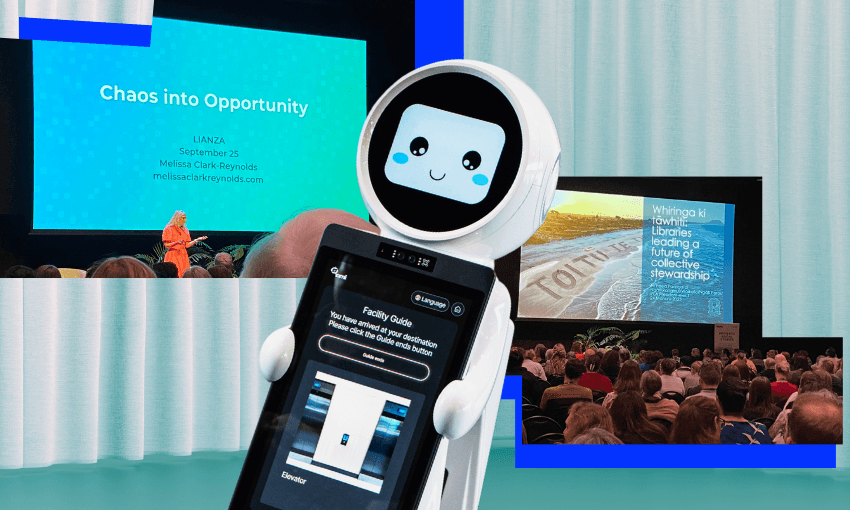

Clark-Reynolds’ keynote (titled “Chaos into opportunity”) was the first up on the second day of the LIANZA conference. The event filled Wellington’s Tākina centre with expertise from all across the motu for three days and over 75 sessions. Topics spanned prison libraries, sustainable collections, automated collection management tools, banned books, libraries after hours and climate action. But the subject with the most hefty coverage was AI: presumably because if anything is about to upend libraries and information systems, it’s that.

Clark-Reynolds’ keynote began with a story that nestled herself firmly alongside the experiences, and assumed passions, of the room: she talked about how she was reading by three years old and by five she was taking the bus to the old Wellington City Library building and skipping down the stairs to where the children’s librarian would be waiting for her with a fresh pile of novels. So, basically she is Matilda – unusual, unusually bright and hungry for stories.

I found her talk a fascinating dance: running headfirst into AI (creating an avatar of herself as described above) and then swerving away at the last minute. She was sure to show how AI can and is being used, but also its many pitfalls. For example, she said that while AI has affected 92 million job losses, it has also created 170 million. But, of those 92 million losses the majority are jobs typically held by women: she spoke about the porn industry as a sort of keystone industry, with voice work already nullified by AI replacements (for phone sex and the like).

She used the now-defunct ice cutters of America – who tried to stop freezer-made ice from being called “ice” (they didn’t think it was legit given it wasn’t harvested from natural formations) – as an example of scared people trying to slow down innovation. She argued that visual art made using AI was simply “new” in the way that using metal tools over stone might once have been new and unsettling. She also took care to say that AI does need regulation so long as we’re regulating the right way; and later showed a terrifying graph that revealed that Reddit is the number one site scraped by AI. She used the example of Gen Z using AI as a therapy tool to suggest it’s OK for us “not to know” when it comes to assessing the pros and cons.

The parting provocation was about whales. “We’re so human-centric!” she said. We AI ourselves, but what about whales – they could tell us about the oceans. Dogs could tell us how to farm better! My overall takeaway was that while Clark-Reynolds is trying to get us to see AI as a strange new potential – like an ultra-bright child who had to fight to do computer science at school, like she did –she also doesn’t want to wholeheartedly advocate for a flawed tool that is prone to hallucination, bias and taking women’s jobs.

In the short break between the keynote and the breakout sessions I went in search of the coffee station, but was waylaid when I came face-to-screen with a robot. A human-sized contraption at once futuristic and retro: it resembled the bot from Lost in Space blended with the rounded, whitened-teeth-bright curves of Eva from WALL-E. Its name was Romi and was designed by Bibliotheca to assist library users with returns, checkouts, finding books and locating materials. It can take photos and send them to you. I sidled past Romi, and the coffee, to get to the breakout session on school library services.

This session was in the same, huge room as Clark-Reynolds’ keynote but this time only a thin smattering of people were in attendance. Elizabeth Jones, director of literacy and learning at National Library of New Zealand, opened the discussion by giving some key, depressing facts about the state of school libraries in New Zealand:

- They’re the least supported and resourced of the library sector despite being among the most impactful

- There are no government regulations, policies, standards or requirements for school libraries in New Zealand

- There is a high level of disparity among schools

- This year marks the 25th anniversary of the School Libraries Association of New Zealand (SLANZA)

Jones’ colleagues Trena Lile and Miriam Tuohy then tag-teamed for the rest of the presentation which largely showed how they collect their research (their own, and commissioned research like this from NZCER) and what they’ve found. The piece I found most alarming was the fact that research is not only throwing up a marked decrease in reading and knowledge of books among students, but among their teachers, too.

“We are crying out for advocacy,” said Jones. “School libraries can’t just be a nice-to-have. We need to use this research as a lever.”

The closing keynote of the day was given by Te Paia Paringatai (Waikato, Ngāti Porou) the first Aotearoa president of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). Paringatai talked about her early encounters with libraries, seeing their “invitation to curiosity” in the same way that her kaumātua invited her to learn through their “living stories”. But, she said, she noticed a stark silence – no mātauranga, no te reo Māori. That was when she realised libraries could be so much more.

Paringatai engaged the full house in a series of questions: we had to think about them and share our thoughts with the people next to us. It was the last session of a very full programme but the clamour of the crowd told of unexhausted enthusiasm. What does regeneration mean? One person spoke about regeneration in the form of daily waiata for staff; another about reclaiming indigenous place names; another about a new home-library service for rest homes.

Paringatai’s closing thoughts included an urge to think of local issues in a global context: she was clearly passionate about the work of IFLA and its potential in sharing solutions across country lines and cultures.

The overwhelming impression I had from the LIANZA conference was of a world in flux. Like the singular robot that wheeled itself sort of aimlessly past exhibitor stalls advertising Oxford University Press and the National Library of New Zealand, there was a sense of old and new worlds trying to figure each other out – an undertone of adapt to the chaos, or die like ye olde ice cutters. But given the fact I wanted to attend every single event, and the sheer passion of the people, I left the building with hope there will be enough human minds and hearts to face whatever comes.