How long a graduate takes to pay off their student loan can have a far-reaching financial impact. So how are pay gaps between genders and ethnicities affecting that payback period? Emma Vitz crunches the numbers.

Previously, I took a look at student loans and how long it would take for graduates in each industry to pay off the average loan. The construction and transportation industries came out on top, and graduates in all industries were paying off their student loans more quickly than they did in the past. This was true even though the average student loan for three years of study increased from $28,536 in 2009 to $41,457 in 2020.

Now I’d like to look at differences in payback periods by ethnicity and gender.

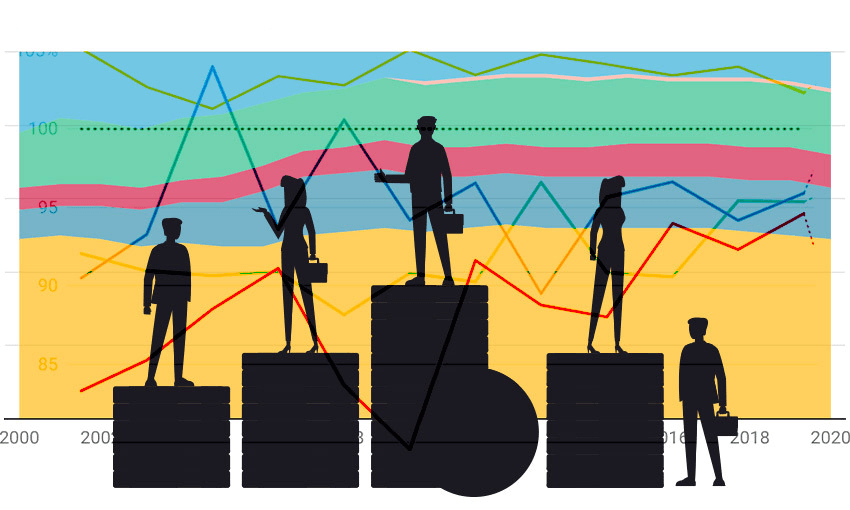

The demographics of student loan borrowers in New Zealand have shifted slightly over time. In 2020, 62% of people taking out student loans were female, a number that has been rising since records began in 2000, when 56% of borrowers were female. In terms of ethnicity, the proportion of borrowers who are Asian and Pacific has also increased over time.

Taking the average hourly wages earned by ethnicity, gender, and age group, I’m able to work out how long it would take a given student to repay the average student loan. Remember, this is done by the IRD docking 12% of your gross income above a certain threshold. I’ve also applied a “degree premium” to the income numbers, which is the additional amount earned by someone with a degree compared to a lower qualification.

Female students graduating in 2009 would have taken just over eight years to repay the average student loan, while male students would have taken 7.75 years. By 2020, this difference in payback period had shrunk to a month. We even had a brief, magical moment in 2019 where the genders were equally burdened with debt.

The differences in payback periods by ethnicity follow a similar trend, although the gaps are larger at all points in time. In 2009, European students would have taken 7.67 years to repay the average loan, while for Pacific students it would have taken over a full year longer. By 2020, the largest gap between ethnicities was four months.

These differences are driven by differences in income, since data on the differences in loan balance by ethnicity aren’t available. So what are these underlying trends in income that have me projecting a decrease in the payback periods?

Between men and women, the gap in wages for 25-29 year olds has been small, hovering around parity, although since 2014 men have consistently earned more than women. Since I’m interested in how long it takes to pay off a student loan, I’ve only included 25-29 year olds in these calculations as a proxy for those people most likely to be paying off a student loan. There is evidence that men and women start off earning a similar amount, but the gap widens as they get older, so this pattern may not hold across all age groups.

The pay gap between ethnicities has also decreased over time, although it is larger to begin with and remains clearly in favour of Pākehā, who earned between 2.5% and 5% more than the overall average from 2009 and 2020.

Some of the largest strides towards closing the ethnicity pay gap have been made by Pacific peoples, who earned 17% less than the average in 2009 and only 5% less in 2020. In 2009, Māori workers earned 8% less than average, while Asian workers earned 10% less. By 2020, both of these ethnic groups were earning 4% less than average.

Looking at the impact these gaps have on something like a student loan starts to show how pay differences can snowball over time. The longer it takes to pay off a student loan, the longer someone might have to put off buying a house, investing or saving for retirement. This is time that eats into their ability to build financial stability, and maybe even locks them out of certain choices forever.

So should these numbers give us hope that we are moving closer to pay parity? I think so. However, we’ve still got some significant room for improvement, especially when it comes to the ethnicity pay gap.