Last week, the prime minister issued a swift ‘Ah, no’ when asked about Tama Potaka’s use of the word ‘austerity’. Here’s why the word has become politically toxic in recent times.

I’m seeing the word austerity crop up a bit. Why?

During these challenging economic times and conversations about fiscal “snakes and snails” and cuts to the public service, austerity has crept into commentary recently. The word itself doesn’t have a very PR-friendly backstory, originating from the Greek austeros, meaning ‘‘harsh”, ‘‘rough”, ‘‘bitter”. Austere, the adjective, can be used to describe, say, Kim Kardashian’s beige house.

So it’s bad design choices?

In the political economy, austerity is a term to describe limiting government spending, usually used by conservative governments, often as a response to an economic crisis where debt has risen beyond the revenue they receive. It might involve cutting spending on public services and raising taxes. It has taken on the same fearsome quality as saying “Candyman” in the mirror three times. Many, especially those who’ve lived through eras of austerity in modern times, would argue that’s justified. Politicians, including those in New Zealand, generally avoid saying it, an observation made recently by journalist Andrea Vance and columnist Vernon Small. In 2013 during the Greek debt crisis, German chancellor Angela Merkel got deeply irritated when asked about austerity, saying, “I call it balancing the budget. Everyone else is using this term ‘austerity.’ That makes it sound like something truly evil.”

So politicians don’t say the word at all?

Well… government minister Tama Potaka said it four times in an interview with the AM Show’s Lloyd Burr last week, prefacing it with the word “fiscal”, which doesn’t really take away any of the associated bad mojo. Burr’s eyebrows shot up to the lighting rig. Prime minister Christopher Luxon issued a prompt “Ah no” when asked if he agreed with Potaka’s assessment that the government was focused on “fiscal austerity”. To understand why, read on.

I am still reading. How did the word become political?

Some date it to 17th-century philosopher and father of liberalism John Locke. That was a very long time ago. For more recent examples of austerity and why it’s become so politically unpalatable, particularly in modern western democracies, we head to the United Kingdom and Europe.

What happened there?

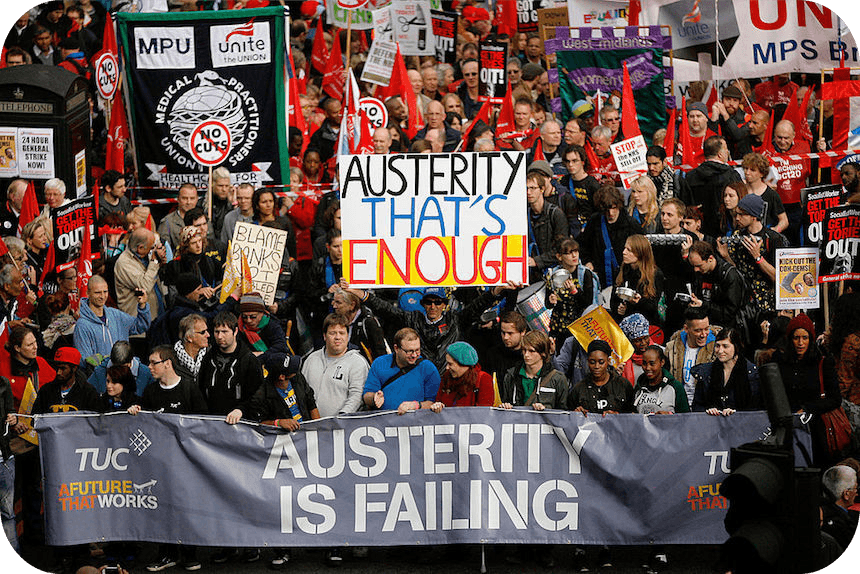

Conservative Party leader David Cameron actually declared an age of austerity in the United Kingdom in a speech in 2009, saying, “the age of irresponsibility is giving way to the age of austerity”. Anti-austerity protest movements grew across Europe and in the UK, asking why everyday people, rather than big banks, for example, were left carrying the “moral duty” of economic repair. Significant spending cuts were made to welfare, education, health and policing. In 2018 Theresa May declared that “austerity was over”. Before a lettuce outlasted Liz Truss as Britain’s prime minister in 2022, she faced accusations of accidentally returning the country to austerity. Faced with similar calls more recently, current UK prime minister Rishi Sunak has strenuously denied them, saying they are “simply unfounded”.

What was the impact of austerity policy in recent times?

Proponents of lower government spending and “belt-tightening” might argue it doesn’t matter what you call it, it’s necessary. A lot of economists have debated the impact and effectiveness of austerity policy. Perhaps the most logical origin of austerity’s contemporary toxicity comes from those who experienced it and still do. Following a decade of austerity measures in Greece, Unicef said that in 2017, 36.2% of children were at risk of poverty. In the United Kingdom, a UN expert said that austerity policies were directly linked to a rise in poverty. While spending on the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK was initially “protected”, a government-commissioned report in 2022 found that a “decade of neglect” had “weakened the NHS to the point that it will not be able to tackle the 7 million-strong backlog of care”.

Have we had ‘austerity’ recently?

We’ve had zero budgets – a phrase that cropped up in Burr’s interview with Potaka after the minister said “fiscal austerity”. In 2011 and 2012, in the wake of the Christchurch earthquakes and the global financial crisis, both budgets were billed as “zero budgets”, with spending in areas like the rebuild, justice and health enabled by “getting better value from public spending” and savings in the billions in other areas.

Are we living in an austerity era now?

We don’t know what the government’s budget, which will come out on May 30, will look like. So far, commentary about debt tracks and government books has been prefaced by words like “relative”, “a form of”, and “implausible” when using the word austerity. The Herald’s Thomas Coughlan described Treasury forecasts in June last year as showing “the government’s ability to bring inflation down, bring the books back to surplus and stick to its debt rule relies on a decade of implausibly austere budgets”. Politics lecturer Toby Boraman said of last year’s election results, “a form of austerity was always going to win”. Andrea Vance wrote that despite the a-word having a bit of a resurgence around the world post-pandemic, it was “like trickle-down economics”, “consigned to the scrap heap of bad policy in the years following the global financial crisis”.

Following his “Ah, no” response to Potaka’s comments about austerity, Luxon explained that the government was instead focused on “a culture of fiscal discipline”.