One in nine tamariki live in households that forgo basic necessities to make ends meet – and during the coldest months, that can have serious health effects. One high-end designer has teamed up with Middlemore Foundation to help.

Summer has disappeared. People are busting out their heaters, fitting electric blankets to mattresses and finding hot-water bottles from the depths of their linen cupboards. Slippers and Uggs are replacing jandals, Birkenstocks and Crocs, trousers and hoodies are taking the place of T-shirts and shorts. The days are getting shorter, the nights longer. Winter is near.

The coldest months of the year are tough when it comes to household expenses, especially for those experiencing material hardship. Defined as households deprived of more than six of the 17 basic necessities most people regard as essentials, material hardship means children are 16 times more likely to endure a cold house than those living in healthier households. Material hardship is experienced by one in five Māori tamariki, and one in four Pasifika children.

Measuring poverty is a complex task – there’s no single standard that Stats NZ can use to ascertain how big or small it is. Instead, it relies on a multi-level, multi-measure approach legislated by parliament. The household economic survey, on which child poverty statistics are based, canvasses only a representative sample of people so ,some uncertainty exists each year about the true extent of poverty in Aotearoa.

When it comes to poverty in Auckland, the country’s economic engine is a tale of two cities – the haves and the have-nots. According to the Auckland Prosperity Index, which measures the prosperity of all 21 local boards based on a suite of measures covering skills and labour force, household prosperity, and economic quality, all five of the south Auckland boards – Mangere-Ōtāhuhu, Manurewa, Maungakiekie-Tāmaki, Ōtara-Papatoetoe and Papakura – had the least wealth in 2020. By contrast, the most prosperous residents lived in Albert-Eden, Devonport-Takapuna, Orākei, Upper Harbour and Waitematā boards. The results haven’t changed since the index’s maiden report in 2018.

At the coalface of this deprivation is Middlemore Foundation, which funds initiatives in health, homes and education in the southern, eastern and rural areas of Tāmaki Makaurau that make up Counties Manukau DHB. The registered charity works with its namesake, Middlemore Hospital, to ensure children can be treated for preventable illnesses in the community without having to seek emergency care. Most of, if not all, those preventable illnesses relate to a child’s ability to breathe, and are compounded by living in poorly insulated, draughty, mouldy houses. “It’s straight poverty in that sense,” says the charity’s chief executive, Margi Mellsop.

The foundation can’t immediately prevent kids from needing to visit the hospital for respiratory illnesses – that’s a longer-term goal, she says. So until that’s achieved, it works to raise funds and provide opportunities to people keen on making a difference, including teaming up with sustainable knitwear brand Standard Issue to keep kids warm this winter.

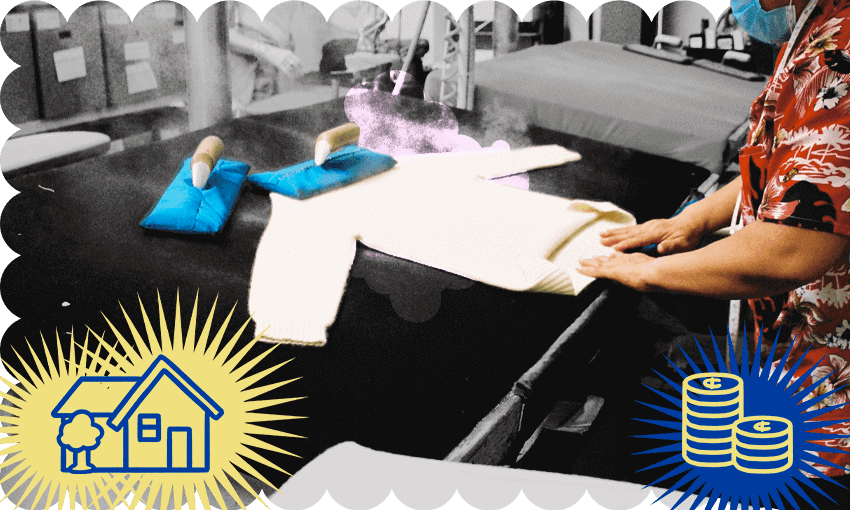

The “Jumper for Jumper” initiative sees the label donating one woollen jumper to a kid in need for every Standard Issue jumper a customer has purchased online or in its Newmarket store. Now in its third year, and running from May 1 until the end of July, the initiative also invites people to buy a child’s jumper outright for $30, which covers Standard Issue’s materials and production costs in knitting and donating it on their behalf. All jumpers are manufactured in yarns made of at least 80% wool, knitted according to a pattern the label made, and come in whatever colours it has access to.

Most “buy one, gift one” initiatives require customers to purchase a product in order to make a donation, but Standard Issue encourages people to buy a jumper for tamariki without having to commit to buying a piece themselves, at a typical cost north of $200. Broadening access has been critical to increasing the number of donated jumpers, says label owner Emma Ensor. It’s been common for some customers to outright buy a dozen $30 jumpers for around the same price as one of their $349 funnel neck jumpers. “What we’ve always intended is that we just want to go in and do well by a community,” she says.

In passing on the clothes, the foundation works mainly with schools and early childhood education providers in areas where deprivation is at its highest, says Mellsop. To some people, an initiative like “Jumper for Jumper” – where warm clothes are donated to people whose circumstances otherwise remain the same – can still come across as an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff. Mellsop believes that perception has become a “disparaging” description of the fundamental purpose that charities, like Middlemore Foundation, serve by helping those in immediate need. She accepts the government has a job to do, in reforming the many, complex systems that feed into poverty, and that the charity sector must continue to advocate for improvement. But until it materialises, the foundation will continue to act as a stopgap.

Its assistance isn’t going away any time soon. Aotearoa is heading into a crisis so an ambulance is needed at the bottom and the top – Mellsop urges those who can afford to donate to reach into their pockets, “because those kids are going to end up in hospital this year. Their mums and dads will need help to pay their electricity bills. That is the reality.”

Last year, the initiative generated nearly 830 jumpers for donation – up from the 350 donated in 2020. The goal this year is at least 1,600, and double that for every winter to come. Ensor admits it’s ambitious, “but we want to go for it”. And should South Auckland become “saturated” with Standard Issue jumpers, she has assured the foundation it will look at other ways it can help. “We’ve got no end date,” says Ensor, a comforting promise to those who need it most this winter.