Were a group of Māori men from Parihaka in Taranaki really held in a Dunedin cave in the late 1800s? New research by museum curator Seán Brosnahan seems to have finally revealed the truth.

This article prompted a response from Ngāi Tahu kaumatua Edward Ellison, which can be found here.

Shore Street, on the Dunedin harbour, marks the turning point of two different worlds. On one side, the busy machinations of industrial work sites, large grey factories and offices. On the other is Portobello Road, a quiet single lane road which curves around a tranquil lagoon, before stretching out along the harbour’s edge to albatross and seal colonies on the peninsula.

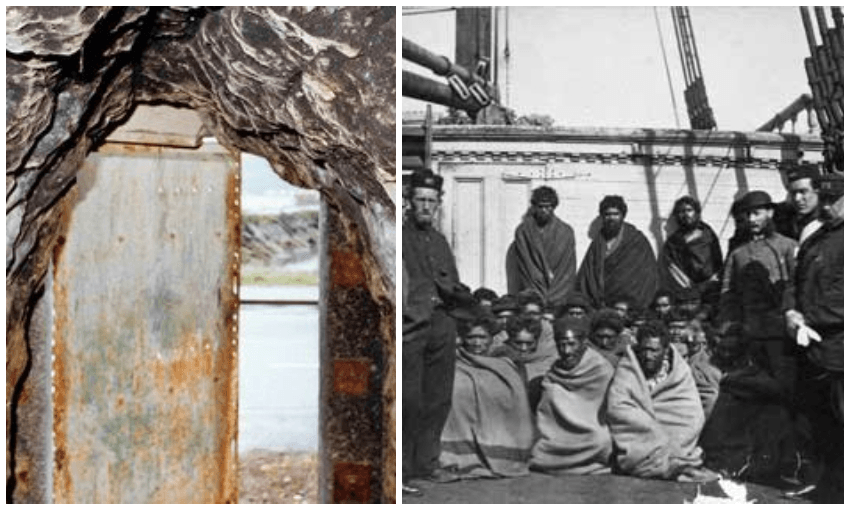

Cut into the hill at the turnoff to the peninsula is a heavy iron door, rusted by the years of sea salt and southern weather. It’s been kept locked for decades.

Very few have ever seen the inside, but the rumours of what (or rather, who) was kept in the man-made cave behind it have spread throughout the city.

An airport shuttle driver points it out every time he goes past. “That’s where the Māori prisoners from Parihaka were held. They built this road across the harbour, and at night they chained them up inside.”

Author and member of the New Zealand Order of Merit Elspeth Sandys wrote of it in her memoir, What Lies Beneath:

“I never did get to see inside that cave. When I learned, years later, that Maori prisoners, guilty of nothing more than peaceful protest, had been held captive there in the late nineteenth century, chained to its walls for months at a time, I felt, as I have since the earthquakes, as if the ground under my feet was no longer solid.”

After the cave was uncovered in 1985 behind overgrown foliage and rubble, Governor-General Sir Paul Reeves, himself a descendant of Māori prisoners kept in Dunedin, requested to be shown through.

Inside the narrow entrance, they found a wider main area, with a bench seat cut into the walls, side chambers about the size of a prison cell, and an iron stake driven into the ground. The roof was blackened, and the ash of decades-old fires lay undisturbed in a hollow in the centre.

Since then, dozens of descendants of Taranaki iwi have come to the caves on pilgrimage to follow in their ancestors’ steps.

In 1987, a one tonne stone from Taranaki named Rongo was brought down and laid near the caves, in honour of the Māori prisoners who died there. The caves were declared a Māori traditional site under the Historic Places Act, and in 1994 the site was made a category 1 historic place on the Historic Places Trust Register, signifying a place of ‘special or outstanding historical or cultural heritage significance or value’.

There was only one problem. It’s not true.

None of the Parihaka men ever worked on or near Portobello Road.

No prisoners were ever kept in the caves.

The caves didn’t even exist at the time.

Toitū Otago Settlers Museum curator Seán Brosnahan was asked to look into the history of the Parihaka men in Dunedin. His research became the most extensive report into Māori prison labour in Dunedin to date, not only dispelling myths but uncovering previously untold truths.

There were two main groups of men from Taranaki sent down to Dunedin as prisoners. First, in 1869, were the men from Pakakohi, a group of 74 who had supported Titokowaru in an uprising against the Crown over unjust confiscation of land in South Taranaki. They were originally sentenced to death for high treason, but had their sentences commuted to imprisonment and hard labour.

The men were largely very old or very young, and in poor health. One man, named Waiata, died just minutes after reaching the Dunedin Gaol. Over the 25 months they spent in Dunedin, 18 men would die, mostly of pulmonary conditions such as bronchitis and tuberculosis, exacerbated by the damp prison conditions and the dormitory sleeping arrangements.

Ten years later, in 1879, the Parihaka Ploughmen were sent to Dunedin. Their village was a centre for non-violent resistance to government confiscation of land. When the government started surveying the land for sale, the Parihaka men, led by Te Whiti, disrupted them by ploughing and fencing land occupied by settlers. Some 200 men were arrested.

One hundred and thirty-seven men in total were sent to Dunedin, in two separate groups. The first group were sentenced to two months’ hard labour, with an additional 12 months’ imprisonment added because they couldn’t pay the ₤600 surety for good behaviour. The second group were to be held indefinitely without trial.

Three of the Parihaka men died in Dunedin Gaol, all of tuberculosis.

Ultimately, any ideas the government had that the arrests would be a deterrent to the Parihaka resistance proved groundless. By June 1881, almost two years after the first prisoners were sent to Dunedin, they had all been released and returned immediately to Parihaka. In November that year the New Zealand government invaded Parihaka with an armed force of 1600 troops, evicting and arresting the passive-resistance leaders and destroying hundreds of homes.

It is considered one of the most shameful acts in our nation’s history.

The hard labour the Pakakohi and Parihaka men were forced to do while in Dunedin provided infrastructure and maintenance to the burgeoning city.

The men from Parihaka had a relatively short hard labour sentence, but they did significant work cutting a connection from Maitland Street to Princes Street, and building portions of the main road from Dunedin to Port Chalmers. It is clear from the records that they never did any roadworks projects in Anderson’s Bay or anywhere near the Shore Street caves.

“I’m confident no one from Parihaka ever set foot on the Otago peninsula,” said Brosnahan.

The Pakakohi prisoners had a far more significant impact on the city. The crew worked a total of 22,447 days of labour, and built Maori Road (which was named for them), significantly widened Anderson’s Bay Road, and did major earth-moving projects around the site which is now the University clocktower building. Their biggest project was developing the sports grounds at what is now Otago Girls High School. A memoir from the school’s 50th jubilee remembered the Māori prisoners fondly. “The sympathised with the girls because they thought they were fellow prisoners, they were all stuck there together.”

The Pakakohi men did work in Anderson’s Bay, near the cave, but it was a very minor part of the total work they did – just 132 days worth of labour, less than 1% of their total work.

Until now, little has been remembered, or even known, about the details of exactly what those men did during their time in Dunedin. The urban legend of the Shore Street caves served as a juicy, scandalous story that filled in the gaps of collective knowledge.

The mission to uncover the full story of Māori prisoners began in 2014 after Dunedin man Steve McCormack put a set of leg irons up for auction. He claimed they were found in the caves and were used to shackle the Māori prisoners while they were kept there overnight.

Dunedin Mayor Dave Cull stepped in and paid $3,900 for the shackles to shut the auction down, and asked Seán Brosnahan to investigate the origin of the shackles.

They were a con. “It was complete bullshit,” said Brosnahan. “The guy was a fraudster.”

The Dunedin Gaol kept extensive records of when prisoners were placed in shackles, and none of the Māori men are ever mentioned. Besides that, the shackles were far too big and heavy to fit around a human ankle anyway – they appeared to be Middle Eastern in origin, and were probably used on camels or perhaps Clydesdale horses.

But the standout lie of the whole scam was McCormack’s claim of where he found the irons. He got the cave wrong – he claimed he found them not in the Shore Street cave, but in another cave slightly further along the harbour on Portobello Road. The only problem was that cave was a well documented powder magazine, with 700 kegs of gunpowder inside it while the prisoners were working on the road. There is no chance any person could have been kept inside the cave, even for a short time.

That led Brosnahan to try finally get to the bottom of the Shore Street cave rumour. “It’s very popular and it’s a thing that’s got a small kernel of truth and has kept growing,” he said.

“It looks like a prison cell, and it feels very creepy if you go into it” Brosnahan said. He was never officially allowed to gain access but did manage to have a look through when a colleague noticed the lock on the door was broken. “I can see why people would easily imagine it was a prison cell.”

He looked through every piece of photographic and cartographic evidence from the time, as well as tomes of jail records and community board minutes, to determine if there was anything to the story.

Records on the construction of Anderson’s Bay Road, which was the project the prisoners were supposedly kept in the caves for, are quite extensive because of a controversial legal case at the time.

Matthew Holmes, a wealthy landowner and politician, objected strongly to the works because he worried it would silt up the bay and decrease his land value. He took the superintendent, the jailer, and the chief warden to court to stop the work.

The court documents and prison records included specific references to the Pakakohi prisoners being ferried across the harbour by boat every day, so they definitely never stayed at the work site overnight. There was also a proposal to build a small shed for the men to shelter in, which was rejected due to cost. This again would suggest that the cave was never used – why would they need a shed if the cave was being used as shelter?

There was some suggestion that the cave could have been excavated by the prisoners after the proposal for the shed was denied, but that was disproven by a letter from the landowner, William Henry Cutton, founder of the Otago Daily Times and later a member of parliament. Permission had to be sought from him to build on the land, and he gave his approval, saying:

“I have no objection to your making a road in front of my land between the Bayview Inn and Andersons Bay provided the road be made on the beach and not cut out of the land.”

If he wouldn’t allow the road to be cut into the hill, it seems incredibly unlikely that he would have approved the construction of a man-made cave.

The cave was never used to house the prisoners, and the reason is simple: it didn’t exist. The cave itself appears to have been built post-1900.

The structure never actually makes a formal appearance in historical records until 1986 when it was discovered and immediately assumed to be a prison cell. There’s no construction records or details of it being used for any business purpose.

But a 1901 military survey of the area provides a clue. It is just about as detailed a topographical map as you could ever see; it shows every little bush and worker’s shed, and importantly, every cave. But there is nothing on Shore Street. It clearly shows the powder magazines on the other side of the harbour, and other similar features, but the side of Shore Street is conspicuously blank.

“My inference from that is that there was nothing there,” Brosnahan said. “Now maybe it was missed, but you can see that everything else is there. And because it was done for military purposes, a structure like that, that had potential military use, I doubt they would have missed it.”

The earliest evidence of the cave existing is from an undated photograph of the bridge across the Anderson’s Bay inlet. The bridge in the photo was replaced in 1912, putting the likely construction date of the cave between 1901 and 1912.

“I haven’t been able to get to the bottom of what it was for, that’s the one enduring mystery. And I have spent a lot of time trying to determine that. It’s kind of like looking for a needle in a haystack, but you’ve got to find the right haystack before you can find the right needle.”

Brosnahan trawled extensively through relevant records of quarries and similar nearby powder magazines, and he is confident it wasn’t used for storing gunpowder (although he couldn’t 100% rule it out).

There were a lot of public works going on in the area at the time, so the cave could have been built for quarrying purposes, or storage, or maybe even a shelter.

But the most likely reason it was built, according to Brosnahan, is milk.

The Dairy Industry Act 1908 changed regulations around milk production and storage. Farmers could no longer just leave tankards out on the side of the road to be picked up; now they had to be kept in cold shelters.

And we do know that the Shore Street cave was definitely used to store milk at one point – a local archaeologist recorded that his mother-in-law remembered milk being kept in the cave.

So it’s very likely that this was the reason it was built. The location, the fact that it is man-made, and the timeline all make sense. But it still can’t be entirely ruled out that it was a repurposing of an existing structure, because there still aren’t any records from the time documenting its construction.

Part of that may be because of its location in what Brosnahan calls Dunedin’s “Bermuda Triangle” – a strange cross-section of different local body organisations, where it’s not exactly clear who has jurisdiction over what.

So while the origin of the cave is still a little unclear, it can be said for sure that the story of Māori prisoners being kept inside is nothing more than an urban legend, one that got so out of hand it was officially recognised by the government.

The myth turned out to be based on a hazy recollection by Otākau kaumatua George Ellison, who was interviewed in 1985 by historian Bil Dacker about his grandfather Raniera Erihana’s involvement with the prisoners during their time in Dunedin.

But the transcript of the conversation was anything but clear when it came to the caves. “Apparently they used to house them there at night time I think….” Ellison said. “I suppose it was better than taking them wherever they were… I don’t know at all.”

Regardless, it was quickly picked up and reported by newspapers as fact. From there, it grew legs and became part of the tapestry of the city’s history for 33 years.

It has become a powerful symbol of Māori deprivation and injustice, and while that did certainly occur, it happened across the water at the prison, not in the caves.

“It’s unfortunate because it has distracted attention from the real experiences. The reality is powerful, and it’s unfortunate that the focus has been on this fantasy. It’s a misapprehension that’s expanded and become an urban myth,” Brosnahan said.

Dunedin Mayor Dave Cull has travelled up to Taranaki to present some of Brosnahan’s research, and Brosnahan plans to present his latest findings there later this year (he revealed his discoveries at a public event at the Otago Settlers Museum on Sunday). He hopes it has the potential to be a “positive out of a negative” in terms of Otago’s relationship with Taranaki and its iwi.

“It’s a bad story, there’s no two ways about it. Dunedin took advantage of a whole lot of Māori prisoners during the period they were here. But I think the good thing about this research is that it’s a really nitty-gritty day-to-day record, which is why I think it will be useful to the people in Taranaki when they really want to engage. There’s so much detail in this about what they ate, where they worked, how long they worked.”

But despite all his work, he accepts that the legend of the cave will likely live on, no matter what his research turns up.

“I know there’s some people that will find it very difficult to let go of that cave story, because it’s very appealing. The prison doesn’t have the same sexiness as a cave.”

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.