As more and more distractions fill our roads, Aucklanders still insist on flouting the red man.

It’s a busy, busy day on Queen Street and everyone has somewhere to be. Construction workers walk three abreast, a chorus line of high-vis and hard hats, past suit-wearing businesspeople taking urgent calls. Teenagers in big pants dodge tourists lugging telephoto lenses. The momentum grinds to a halt as the lights change, the little red man blinking threateningly. “Don’t even think about it,” he warns, signalling thou shalt not pass. But pass people do, seizing their mortality in their own hands, past all of the cars, trucks, vans and Ford Rangers.

Some, understanding the urgency and, perhaps, the risk of getting caught, decide to dash across quickly, fast-twitch muscles engaged. Others take their time. Their rebellion isn’t just against the laws of physics and Part 11 of the Land Transport (Road User) Rule 2004, it’s against time itself. Then there are the strategists, familiar with the light phases and seconds between changeovers, they’ve got it all down to a fine art.

The very boldest of jaywalkers just go for it regardless, eyeballing the drivers as they pass, free of shame or regret; they’re not in a hurry to get somewhere, they’d just rather not have a light tell them what to do. Jaywalking is a little act of rebellion. Is that why we do it, to kick back against rules and regulations, or demonstrate unimpeded agency? (OK, maybe Jean-Jacques Rousseau was right, but that doesn’t stop us from stepping off the kerb to freedom.)

As far as crimes go, it might be the easiest one to commit, with little planning required and no collusion. And besides, it doesn’t feel very illegal. And surely a humble pedestrian deserves to go first? They do overseas. In France, motorists are “obligated to yield” to people crossing the street or “clearly manifesting” plans to do so. On Aotearoa’s roadways, where vehicles have right of way, jaywalking is a pastime that transcends race, creed, gender and income bracket; everyone’s got somewhere to be.

Besides, when are you jaywalking (illegal) and when are you simply crossing the road (chill as)? If you’re within 20 metres of a “pedestrian crossing or school crossing point, an underpass, or a footbridge” or ignoring a red crossing light at an intersection, you are indeed breaking the law, and may face a $35* fine. Outside of that you’re all good, just so long as you cross at a right angle to the kerb or road (clause 11.4), meaning no diagonals, zigzags or any funny business. However, cross, or even just walk along, a motorway and you’ll be looking at paying hundreds of dollars.

You’re risking more than a fine though; crossing the road is pretty much playing bullrush, but with cars. Five pedestrians were killed in the first month of 2025. The majority of pedestrian injuries happen on urban roads – usually while crossing – and over half happen within 2km of the person’s home. In Auckland, a third of road fatalities are pedestrians, and the region accounts for 41% of the country’s hospitalised pedestrians.

As New Zealand Medical Journal experts have pointed out, “it is well established that pedestrian and road injury risks are disproportionately borne by tamariki Māori and Pacific children, older people, disabled people, rural communities and residents of socio-economically disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. Many of these groups have lower access to cars but are more likely to be injured by them”.

How fast a car is going when it hits you influences your chance of surviving, and “the survivability of pedestrians involved in a crash with a vehicle has been shown to increase significantly at impact speeds of 30km/h”. Speed limits have gone down, and then (for 1,500 streets) up again.

Crossing a designated shared space is designed to be safer; vehicles have to give way to you, but in turn you “must not unduly impede the passage of any vehicle”. You can’t just stand there, considering the burden of human existence while looking at the Sky Tower, nor can you loiter on designated crossings or roadways. Shared zones encourage a more leisurely speed of all users. There are no kerbs or road markings, but there might be surprising things like seats, bollards and pot plants. The idea is that these create an “intentional level of ambiguity” that elicits caution (and, in some cases, confusion) from vehicles and pedestrians, slowing them down. In these ambiguous zones, cyclists and drivers are “legally required to give way to pedestrians” (though a 2017 report showed Elliot Street motorists only “yielded” to pedestrians 28% of the time).

There have been calls for years to get cars out of the city centre entirely. Plans for pedestrian-only malls (an idea far older than motor vehicles) have been wheeled back, and temporary compromises flirted with – like those funky circles dotted around the CBD. Federal Street and Shortland Street have polka dots designating… something. It’s different, it’s unusual. And that’s the point. Intended as a “traffic calming measure”, they’re designed to slow traffic down, though vehicles legally have the right of way. Not everyone’s a fan. Auckland Transport captured anti-spot sentiment in 2019, noting “almost every person who found the dots confusing or distracting also disliked the painted dots generally” with one respondent likening them to a “playschool aesthetic”.

With enough motivation, you can experience (and flout) all kinds of spaces in one block of the CBD: jaywalk across the Queen Street intersection, ignoring the flashing red lights and turning cars as everyone loves to do, past the zebra crossing and onto the funky polka dots of Shortland Street, dodging confused drivers until you get to Jean Batten Place, a shared zone, where you’ll finally have right of way, freedom.

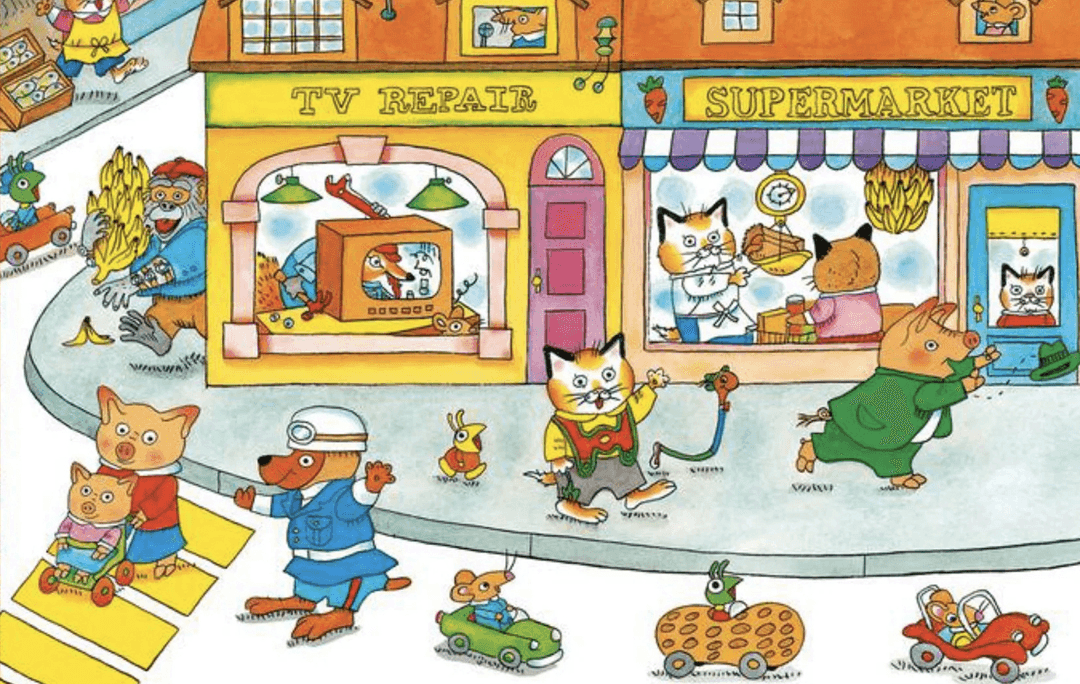

You’re in the thick of things, walking across the city’s bustling streets like a busy, societally engaged Richard Scarry character. For such a real-world activity – stepping in front of thousands of kilograms of metal, glass and rubber going 30km/h, if you’re lucky – there’s a considerable cohort of jaywalkers that are digitally orientated. Earphones in and the world around them silenced, their eyes are locked onto the device in their hands (something important, no doubt). Head down, focused, they walk out onto the road where, faces illuminated by a glowing screen on their dashboards, drivers are focused too.

We do it because it’s convenient and we’re impatient. Certain nothing bad could happen to us, we step off the kerb and into traffic. We assume they’ll stop for us. Should they? Will they? There’s only one way to find out.

*Reported in 2020. The Spinoff has contacted NZTA for current infringement figures.