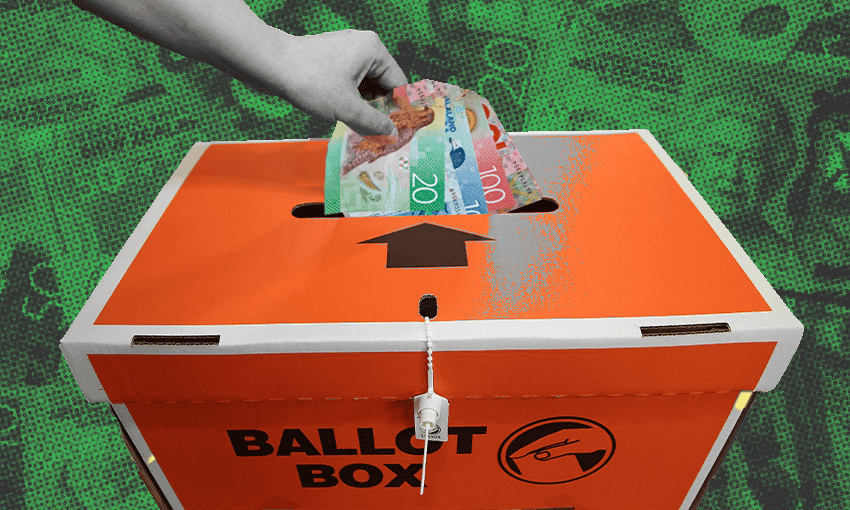

Big business is pouring eye-watering sums into parties on the political right. Max Rashbrooke wonders what it’s getting in return.

A couple of years ago, a National Party contact told me it had “never been easier” to get big donations from businesses. Anger about the Covid-era “fortress New Zealand” policy, combined with an instinctive distrust of Labour, meant wallets were opening wide for the political right.

All this could be seen in the recent publication of political donations returns for 2023. In these returns, parties set out everything from anonymous gifts of $100 at a church hall fundraiser through to the $500,000 that manufacturing magnate Warren Lewis gave National.

Christopher Luxon’s party, unsurprisingly, led the way with a $10.4m total haul. Act, meanwhile, scored $4.3m – a startling sum for a small party, and a reminder of how it was kept on life support throughout the 2010s by dollops of cash from the likes of 80s corporate raider Alan Gibbs. The last of the coalition parties, New Zealand First, declared $1.9m, marking a distinct change from its pre-2020 strategy of using something called the “New Zealand First Foundation” to channel gifts of hundreds of thousands of dollars from wealthy supporters to the party, without actually going to the trouble of – you know – notifying the public.

On the left, meanwhile, Labour pulled in $4.8m, a respectable sum but half National’s amount, while the Greens declared $3.3m. Te Pāti Māori received just $160,000. All up, the left’s tally, $8.2m, was almost exactly half the $16.6m that the right harvested. The trade unions, which in right-wing mythology somehow balance out big business’s influence, contributed a princely $335,000 – less than that single Lewis donation to National.

Why does any of this matter? Because, in politics as elsewhere, money talks. It potentially generates undue influence: giving a political party large sums can induce it to look kindly on you. While there is little evidence of cash directly buying favours, one National donor, interviewed by myself and my Victoria University colleague Lisa Marriott in 2022, said donors had “more opportunity” to get a meeting with ministers.

In the same interview series, another donor, after insisting he enjoyed no special influence, noted that one party leader had come to his house, another was a social contact, and a third “popped in a couple of times and had a chat about life”. This was mentioned nonchalantly – as if the rest of us are constantly fending off politicians’ attempts to come round for dinner – but in fact bespoke a cosy world, evident right throughout our interviews, in which party leaders, fundraisers, MPs and donors constantly rubbed shoulders, with no firewall between decision-makers and coffer-fillers.

Consider this example. Last year, Chris and Michaela Meehan gave National over $100,000. Also last year, their company, Winton, sued the government for refusing to fast-track its Sunfield property subdivision in South Auckland. Also also last year, National MP Chris Bishop issued a press release backing Winton but not disclosing the donation. (Bishop says he was unaware of it at the time.)

Fast-forward to this year, and Winton is one of the companies specifically told it could apply to have its projects expedited under the government’s highly controversial Fast-track Approvals Bill. One of the ministers who would sign off on the fast-tracked projects is Chris Bishop. Another is Shane Jones, who has taken over $50,000 from individuals associated with Kings Quarry, yet another firm on the list for potential fast-tracking. The prospect of ministers ruling on projects run by the people who funded their election campaign seems – how can I put this? – suboptimal.

Donations can also tilt the political playing field. It’s not the case that great wealth can just “buy” an election: a Labour strategist once told me they’d rather have a great candidate with a great message and no money, as opposed to a terrible candidate with a terrible message and lots of money. National’s 2020 election campaign (relevant components: Judith Collins; “Demand the Debate”; more donations than Labour) bears this out.

But, the strategist said, all things being equal, they’d rather have more cash. National’s pollster, David Farrar, concurs: “You always want more money than less, because it gives you options,” he told RNZ last year. Money buys not just advertising but also polling, political consultants, voter databases, travel, venue hire and field organisers. No wonder, then, that the latest international research finds that more money tends to lead to more votes.

It’s worth noting, too, that when it came to donations under $1,500, Labour and Green fundraising ($4.6m last year) largely kept pace with National and Act’s efforts ($5.4m). It was in donations over $5,000 where the right ($6.5m) really smashed the left ($3.1m, a good chunk of which came from their own MPs). It’s that class of donor that made the difference in parties’ reach.

This resource imbalance may also be accelerating. In the three electoral cycles leading up to 2020, National pulled in $19.3m in donations (albeit we have no solid data on donations under $1,500 for that period). In just three years since, it has raised $16.5m. This is, as Farrar acknowledges, “unprecedented”.

It’s unlikely, though, that anything will be done about the problems donations pose. The answers – as set out in the report that Marriott and I wrote in 2022, Money for Something, and reiterated by last year’s Independent Electoral Review – are intellectually straightforward. Cap the amount that anyone can give at around $10,000 a year, ensure that only individuals (not organisations) can donate, disclose the names of more donors, give the Electoral Commission stronger powers to investigate fraud, and spend about $1 per New Zealander each electoral cycle to publicly support political parties.

The problem is that it’s not in National’s interest to implement such reforms, and Labour doesn’t want to wear the right-wing backlash that would greet any such attempt on its part. So we may be left with this stark example of inequality: late last year, Warren Lewis’s workers, many of them on or around the minimum wage, went on strike, asking for a pay rise. That’s New Zealand now, a country where the wealthy can find $500,000 for a party that will advance their interests, but won’t pay their workers a living wage.